In her book, Doctors’ Stories, Montgomery Hunter discusses the pervasiveness of narratives (e.g., diagnosis, cases study, rounds) in informing not only the medical encounter, but also medicine as an institution: “Patients’ stories within medicine are more or less pared-down autobiographical accounts that chronicle the events of illness and sketch out a commonsense etiology. . . Physicians take such a story, interrogate and expand it, all the while transmuting into medical information” (5). Here, I am concerned with autobiographical accounts of illness experiences, whose narrative characteristics challenge the “commonsense etiology” that Montgomery Hunter highlights.

Out-of-the-ordinary accounts of illnesses are mysterious because they challenge the frameworks within which medicine constructs disease categories, that is, not just the biological factors but also the normative and sociocultural frameworks involved in disease categorization (e.g., Engelhardt 1981). Whereas skepticism in science has contributed to the development of medicine, a seemingly automatic interpretation of out-of-the-ordinary accounts of illness tends to discard them as delusional or “all in your head.” I would like to offer a linguistic explanation that suggests a different perspective to this problem. To illustrate my point, I draw on the case of Morgellons disease (MD).

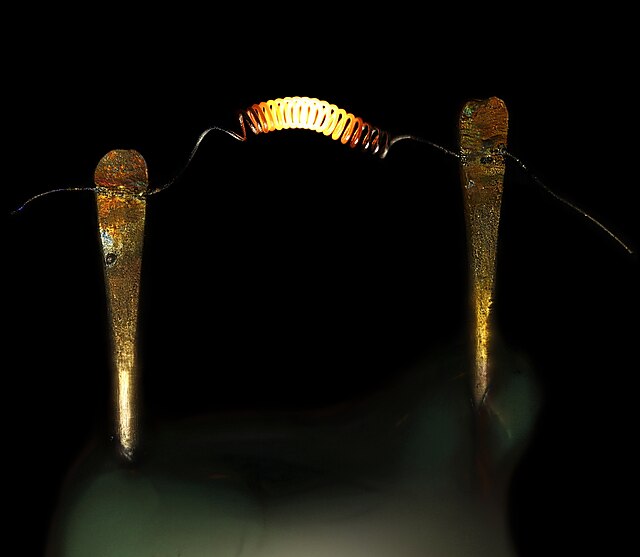

MD is considered “a dermatological condition characterized by the presence of multicolored filaments that lie under, are embedded in, or project from the skin” (Middleveen et al. 71). The causative agent of MD remains unidentified, and despite an investigation launched by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2008, its etiology remains unknown and contested. Dr. Ginger Savely, a medical provider who has been working to legitimize this illness, observes in her book Morgellons: The Legitimization of a Disease that a diagnostic tool of MD is the presence of not only skin lesions but also subcutaneous filaments. Patients often report crawling sensations both within and on the skin surface, which tend to be conceptualized as “bugs moving, stinging or biting intermittently” (115). Visualization of those filaments requires use of specific magnifier dimensions, which may contribute to doctors’ skepticism about the patients’ accounts, such as “parasites have taken over my belly; there are cocoons in my hair; tiny shrimp come out of my skin; my hair moves and has a life on its own” (132).

To justify that their symptoms are not psychiatric, MD patients typically bring multiple specimens to their doctors’ offices such as filaments or cellphone photos, as their specimen or matching sign (see Koo and Lee 2001). However, these samples are treated as confirmation of delusional parasitosis: “Most clinicians have no doubt that what they’re seeing is delusional parasitosis” (Fair 602).

Armando Hernandez, a Morgellons patient, gives the following account of his illness experience in the Kindle publication of his book The Silent Epidemic: Morgellons Disease: “I was shocked to find particles floating in the water. . . . To this day, I still did not know what exactly it was, but it was solid evidence that there was something. I brought specimens . . . and other images to my doctor[s]. . . . They were still stuck to the idea that I was delusional” (emphasis added).

These apparently bizarre accounts of illness experiences certainly convey a defamiliarizing illocutionary force by virtue of their literal, denotative interpretation. The references to worms and parasites seem to constitute what Husserl calls “a slap in the face to all expectations” (263).

Gail Anderson, another Morgellons patient, gave her account on National Public Radio in 2008: “I thought that there were worms in my eyes. I felt that something was eating me—the top of the tissue. And I could see in my left eye that there was something going on. And up inside the inner of my upper eyelashes, I had white spots, all in there, they looked like little, tiny eggs” (24 January 2008).

In our everyday life, worms are not typically associated with humans’ eyes, although they may be in cattle, as in the case of the legitimate diagnosis, Thelazia gulosa. Further, for a person living in sub-Saharan Africa who has been exposed to River Blindness, caused by the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus (WHO), Anderson’s predicament may not seem so strange. Yet, it is the unexpected linguistic collocation of words—between “worms” and “eyes” in Anderson’s utterance—that seems to quickly trigger a sense of defamiliarization or estrangement.

Initially used to explain the artistic function of metaphors and poetry as an aesthetic experience, the terms defamiliarization and estrangement are associated with wondering and a surprising effect rather than delusion or madness. Estrangement allows us to break the routinized forms of perception and see the world anew by focusing initially on the how (or form) to later return to the what (or content) in an oscillating way (Chernavin and Yampolskaya 103). But science, observes Shklovsky (264) tries to overcome the element of surprise. I would add that not only science but also our commonsense view, as dictated by the ordinary cast of mind (see Sacks 1984), precludes us from listening to accounts such as Anderson’s, with a metaphorical frame of mind. Instead, let’s consider these accounts as ways of referring to what seems to have no denotational referent, simply because it is unidentified. I suggest that a phenomenological perspective could help us bring a change of attitude against the discrediting skepticism that these types of accounts tend to elicit.

Estrangement is not reduced to poetic language as poetic language is not constrained to poetry, as Jakobson observes in his Linguistics and Poetics. A phenomenological attitude means, at first, seeing without understanding, which requires a constant renewal of effort, that is, “one has to block one’s natural understanding of the world in order to see it anew” (Chernavin and Yampolskaya 106). Thus, a different interpretation and attitude toward these accounts could be found in trying to block the initial denotational referent of statements, such as “worms in my eyes,” and instead thinking of them in metaphorical or comparative ways, i.e., by blocking the concern about what to appreciate how the person is saying it, to see it anew.

In a study on the history of MD, Middelveen et al. distinguish the case of “delusion” versus “beliefs.” They observe that whereas delusions are intensely held beliefs barely swayed by evidence to the contrary, beliefs could arise from misinterpretations whereby patients interpret the presence of filaments and formication as worms, arthropods, or other infestations. However, given that filaments can be seen in these patients’ bodies with the appropriate magnification and light—thus, producing evidence for the reality of their accounts—Middelveen et al. conclude that misinterpretation is not a sufficient cause for diagnosis of delusional mental illness. Rather, they argue that those accounts are logical speculations: “MD is not a case of fixed belief …, because if filaments are present and they are visible under magnification, then there is medical evidence” (85).

From a linguistic and phenomenological viewpoint, I would like to suggest that patients’ defamiliarizing accounts could be understood as practical ways of categorizing experiences with which we are unfamiliar because we lack sociocultural or physical referents. A fascinating example of the seemingly estranged ways of categorizing original experiences appears in the Report on the First Voyage around the World, a chronicle of the Venetian explorer Antonio Pigafetta. He was on Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition to the Spice Islands in 1519 but concluded with the circumnavigation of the world. In a passage, Pigafetta describes seeing “a misbegotten creature with the head and ears of a mule, a camel’s body, the legs of a deer and the whinny of a horse” (qtd. in Marquez’s Nobel Address in 1982). The denotational reference of this description would tell us that such an animal exists only in Pigafetta’s imagination. However, a metaphorical interpretation would lead us to realize that his “misbegotten creature” was a way of categorizing a novel reality for a European man in a new land, by comparing it with his previous knowledge of experience. Pigafetta’s metaphor was the South American camelid known as llama.

The lesson from this example is that a quick disregard of defamiliarizing expressions as delusional could underestimate the metaphorical and metonymic cognitive skills that patients use to refer to things by comparison, when lacking the referents. As linguist, George Lakoff observes, “human categorization is essentially a matter of both human experience and imagination—of perception, motor activity, and culture on the one hand, and of metaphor, metonymy, and mental imagery on the other. . . . Human reason crucially depends on the same factors” (8). To conclude, the word ‘worms’ does not always denote worms. Yet, the unintelligible for these patients may have a resemblance to it.

Works Cited

Chernavin, Georgy, and Anna Yampolskaya. “Estrangement in Aesthetics and beyond: Russian Formalism and Phenomenological Method.” Continental Philosophy Review, no. 52, 2019, pp. 91–113.

Engelhardt, H. Tristram. “The Concepts of Health and Disease.” Concepts of Health and Disease: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Arthur L. Caplan et al., Addison-Wesley, 1981, pp. 31–45.

Fair, Brian. “Morgellons Disease: A Contested Illness.” Sociology of Health and Illness, vol. 32, no. 4, 2010, pp. 597–612.

Hernandez, Armando. Morgellons Disease: The Silent Epidemic. Newman Springs Publishing, 2020.

Husserl, Edmund. Analyses Concerning Passive and Active Synthesis: Lectures on Transcendental Logic. Translated by Anthony J. Steinbock, Kluwer Academics Publisher, 2001.

Jakobson, Roman. “Linguistics and Poetics.” Language in Literature, Edited by Krystyna Pomorska and Stephen Rudy, The Beknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1987, pp. 62–94.

Koo, J., and CS Lee. “Delusions of Parasitosis: A Dermatologist’s Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment.” American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, vol. 2, no. 5, 2001, pp. 285–90.

Lakoff, George. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. The University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Middleveen, Marianne J., et al. “History of Morgellons Disease: From Delusion to Definitions.” Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, no. 11, 2018, pp. 71–90.

Montgomery Hunter, Kathryn. Doctors’ Stories: The Narrative Structure of Medical Knowledge. Princeton University Press, 1991.

National Public Radio. “Morgellons Disease Is Creepy. But Is It Real?” The Bryant Park Project. Directed by Alison Steward, 24 Jan. 2008, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=18367924.

Sacks, Harvey. “On Doing ‘Being Ordinary’.” Structures of Social Actions: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by Maxwell J. Atkinson and John Heritage, Cambridge University Press, 1984, pp. 413–29.

Savely, Ginger. Morgellons: The Legitimization of a Disease. (Self-published) Kindle: E-book, 2016.

Shklovsky, Viktor. Bowstring: On the Dissimilarity of the Similar. Translated by Avagyan Shushan, Dalkey Archive Press, 2011.

Image credit: Mister rf. “Miniature Light Bults Filaments.” Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0. September 25, 2021