In 1822, Doctor William Beaumont helped heal a young man whose accidental gunshot wound left an open fistula in his abdomen. Reaching into the healed wound, Beaumont later performed experiments that would result in groundbreaking research on stomach acid and its digestive functions.

In 1984, Octavia Butler published “Bloodchild”, a science fiction short story in which a human man ‘impregnated’ with alien eggs undergoes emergency surgery. As the story’s protagonist unintentionally witnesses the abdominal procedure, he learns how the alien reproductive system interacts with human physiology.

While these two scenes could hardly be more different from one another—one fictional, one historical narrative; one interspecies, one intraspecies; one of digestion, one of reproduction—they’re linked as moments of learning inside the viscera. What start as violent abdominal ruptures become opportunities for excavating knowledge. In the vastness of their differences, they tell us something about the intimacies, exploitations, risks, parasitisms, and strangenesses of working with human bodies as pedagogical objects.

A young white man named Alexis St. Martin was accidentally shot in 1822. Beaumont, a military surgeon, takes St. Martin under his care. After the wound heals leaving an open entry into the stomach, Beaumont contracts him as a servant in order to keep his body available for experiments. Across several years, St. Martin leaves and returns to Beaumont multiple times, coming back seemingly out of financial desperation. For Beaumont, St. Martin’s wound solves many of the limitations of cadaver experimentation. The fistula is understood as an unintrusive glimpse into the natural workings of the living body. When he writes about the experiments in 1833, Beaumont minimizes his influence on the wound, describing it forming as naturally as other parts of human anatomy: “[the fistula] terminated as if by a natural boundary, and left the perforation, resembling, in all but a sphincter, the natural anus, with a slight prolapsus” (13). His analogy amplifies St. Martin’s status as cadaveric, an allegedly unmediated empirical body.

If the cadaver represents an extractive model of learning—mining meaning from the inside—St. Martin is both an apex and a disruptive case. St. Martin’s aliveness makes him here available to even more value extraction (see Note 1). Beaumont’s contract with St. Martin (who was illiterate and destitute) not only allows him to experiment on the body but also to extract manual labor; St. Martin would perform the standard tasks of a house servant under Beaumont’s doubled scrutiny as employer and physician. Beaumont’s contracts to contain St. Martin have necropolitical echoes, maintaining St. Martin’s cadaveric state of extractive availability. Beaumont benefits from watching the movement of living physiology, all while attempting to strictly manage the mobility of that body’s life (see Note 2).

The detail that sticks with most people who hear St. Martin’s story is the strangely crude method Beaumont used for testing how quickly stomach acid would dissolve various “aliments” (Beaumont, 33). Beaumont tied food to a piece of string and slowly lowered them into St. Martin’s stomach. Beaumont’s string is representative of empirical precision (or at least its ideal vision of itself): tightly following a thread into the experimental object, targeted, bypassing the messiness of proximity and the thickness of flesh, a clean line from A to B, experimenter to anatomy. Connecting the two men, yes, but moreso spatializing a diagram; it rationalizes the scene like a leader line (fishing entendre inescapable).

But they’re bodies, not diagrams. The two men sat there, suspending and suspended, for hours. The scientific account unsurprisingly elides acknowledgement of this intimacy, of a measured yet suspended temporality (see Note 3). I’m not suggesting we fetishize that proximity but rather ask how it might be scientifically meaningful. That the physician occupies a living body always in relation to the experimental body is here a missing data point. How does the awkwardness, heat of touch, and suspended time shape the knowledge it helped gather? Beaumont records that anger can disrupt digestion—discovered through St. Martin’s discomfort—but what else do we miss by not taking more seriously the proximity and position of the physician’s body to the experimental body, its tableau and choreography? The elision forms part of an ongoing ontology of pedagogical objecthood, where even the living experimental body is perceived as cadaveric, and the cadaver is understood as an object learners can stay distanced from even as they enter it. It contributes to a racial and necropolitical history of touch, intimacy, and violence, where extractive value, (im)mobility, and unstable aliveness/deadness of certain bodies is directly tied to their availability and productivity as scientific knowledge.

Shifting to Octavia Butler, “Bloodchild” implodes relational intimacy at the scene of learning. A human boy named Gan lives in a colony of humans on an alien planet. Having learned that human abdomens can incubate their eggs, the alien species, called Tlic, create a somewhat symbiotic, mostly parasitic arrangement with the humans. At birth, Gan was promised to a female Tlic named T’Gatoi with whom he and his family share a close relationship. At the height of the story, Gan witnesses a ‘birth’ gone wrong, watching T’Gatoi perform emergency surgery when Tlic larvae hatch inside a man and begin eating his flesh.

The abdominal rupture does not lead to intentional experimentation as it does for Beaumont, but it is a scene of learning. They’re both case studies: Beaumont sees St. Martin as a way to understand a generalized universal anatomy, and Gan sees an example of what might one day happen to his own body. For Gan, it is a dramatic coming-of-age revelation, a biomedical anagnorisis. He learns not just physiological possibilities, but also the depth of his relational imbalance—T’Gatoi’s offspring could kill him, a fact she knew but Gan hadn’t fully learned until the body was beneath him. What had thus far been a narcotic-influenced calm and trust between them becomes a disembowelment of rage, fear, and love. Gan at first threatens to break his promise to carry T’Gatoi’s eggs, then rescinds and agrees after he realizes she would impregnate and endanger his sister if not him. Gan’s renewed promise externalizes the intimate motivations that drove St. Martin’s contracts with Beaumont—he, too, it seems (or at least we can reasonably infer) continued to serve Beaumont in order to care for his family.

“Bloodchild” can be read as an inversion of Beaumont’s experiments, bringing out some of the elided intensities of learning inside human bodies. Moments and textures of Beaumont’s story are relocated into Butler’s scenes, turned inside out. Instead of Beaumont’s internal diagram that leads straight into the experimental body, Butler’s narrative is a lush landscape of sensory surfaces, surfacing, and contact. Where Beaumont has to lower his instrument into the corrosive acid securely contained in the stomach (or extract it himself), the corrosive Tlic larvae are uncontained, digesting their way out. Rather than a suspension that ties the physician to the inside of the experimental body, Gan hangs in a drunken haze while laying atop T’Gatoi’s long abdomen, which he twice describes as “velvet” (n.p.). A villous fabric made by cutting a connected weave and turning it inside out, the velvet “underside” is an inversion of St. Martin’s villous stomach lining; now an external, comforting anatomy of the physician figure (T’Gatoi) (n.p.). Yet it also comes to signal a distance and imbalance between ‘physician’ and experimental body. As Gan recognizes that his own body is also going to be the site of experimentation, not knowing if the larvae will hatch destructively in him too, he changes what he first calls just “velvet” into “cool velvet, deceptively soft” (n.p., my emphasis). Her body is awkward, a false promise of care. Like St. Martin, he reluctantly—and largely out of desperation but also out of love—continues his contract as an experimental body.

There’s much more to say about both of these objects and the many problems in comparing them (see Note 4). But for now, thinking with them together opens questions about agency and will, labor and extraction, and proximity, violence, and intimacy when the human body becomes haptic material for the production of knowledge.

Notes

- When St. Martin dies in 1880, his family puts his body out to rot in the sun for several days before burying it deep beneath unmarked stones, fearful other scientists will harvest its extractive value (Macfarlane).

- Beaumont took St. Martin traveling around, using him as “his PowerPoint”, as Mary Roach put it on an episode of Radiolab (“Guts”).

- I’m reminded of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein released in 1818, where Doctor Frankenstein Victor never touches the Creature’s body after he’s brought him to life through intensive bodily contact, puncturing, suturing.

- Importantly, it’s not that literature gives us a fuller story or recovers a voice for the experimental subject. Instead, it helps us understand more about the physiology of medical recording—what functions internally and unseen, what is external, who is feeling, moving, managing what, when, and where. And the historical narrative doesn’t so much provide context as much as it gives a comparative anatomy for understanding scenes of rupture, learning, and the subject positions as experiment/er. In other words, they don’t solve each other, but they provide methods for touching more of what’s inside.

Works Cited

Beaumont, William. Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion. F. P. Allen, 1833. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/2543009R.nlm.nih.gov/page/82/mode/2up. Accessed 5 Oct. 2025.

Butler, Octavia E.. Bloodchild : And Other Stories, Open Road Integrated Media, Inc., 1995. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/jhu/detail.action?docID=1790515.

“Guts.” Radiolab, 2 Apr. 2012, radiolab.org/podcast/197112-guts/transcript. Accessed 5 Oct. 2025.

Macfarlane, Rosemary. “Studying the Stomach.” Wellcome Library Blog, 2011, blog.wellcomelibrary.org/2011/06/studying-the-stomach/. Archived at Wayback Machine, 14 Mar. 2021, wayback.archive-it.org/16107/20210314102523/http://blog.wellcomelibrary.org/2011/06/studying-the-stomach/

Images

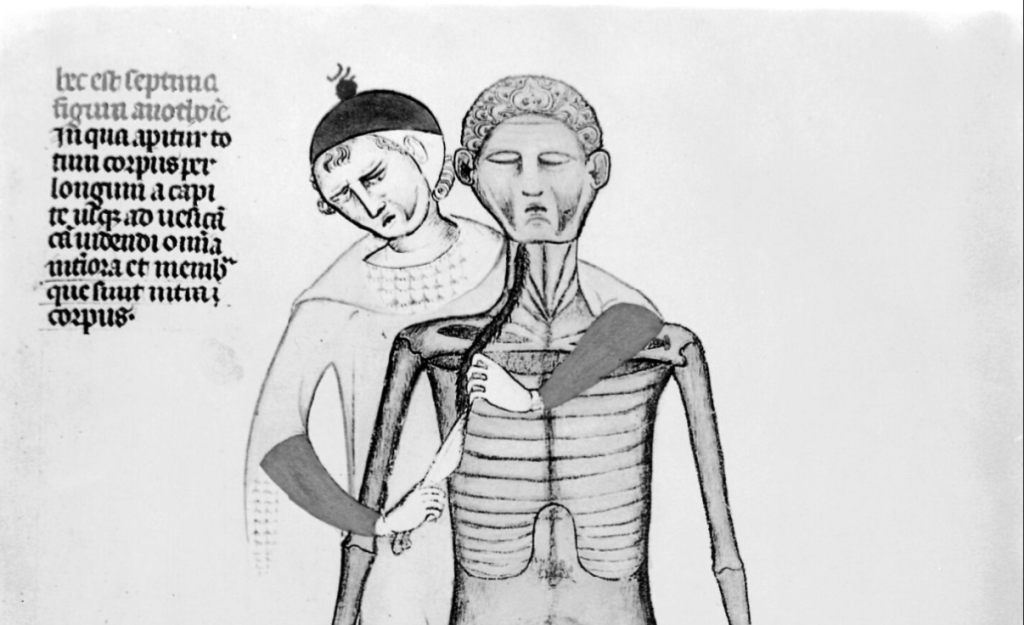

Credit: Guido de Vigevano, miniature anatomical figures, 1345. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)