In an early shot from Lulu Wang’s 2019 film The Farewell, the camera focuses on the movie’s elderly protagonist in what is clearly a medical setting. In Wang’s script, the acting directions state that “Nai Nai sits alone in a hospital gown awaiting her X-ray.” There, “she has a coughing fit.” Although a disconnected arm in a white coat grips her wrist, manipulating her body into a position appropriate for scans, the framing of Nai Nai within the circular opening of the X-ray machine highlights how dramatically central and isolated she is here. As one of the few scenes in The Farewell in which we witness the grandmother solo, silenced but for her persistent hack, this staging marks the clinical equipment as responsible for separating Nai Nai from the boisterous family members who have accompanied her to the doctor’s office and are otherwise present throughout the film. The individualist focus of western medicine on ailment and diagnostic procedure is on full display here.

In this scene, Nai Nai theoretically does not know that she has terminal cancer, though she has been struggling with a cough for months. But despite the proof of cancerous cell presence in her lungs yielded by the X-ray, Nai’s ignorance remains intact. The coverup, or “lie” about her illness is the premise of The Farewell. Choosing to hide the news of their matriarch’s disease progression from her, Nai Nai’s sons and their family members journey from Japan and the United States back to their childhood home in Changchun, China, under the guise of celebrating a cousin’s wedding. In reality, unbeknownst to Nai Nai, the rushed marriage is merely an excuse for the family to enjoy the final days of her life reminiscing (and eating tremendous comfort meals) in the company of distant loved ones.

The film’s other protagonist is Nai Nai’s young adult granddaughter, Billi. Straddling the cultural divide between her own identity as an American woman, her immigrant parents’ generationally distinct perspectives on emotional composure, and her fond memories of summers spent in China with her beloved grandmother, Billi balks at the idea of visiting Changchun and pretending Nai Nai is not dying. Her mother explains to her: “Chinese people have a saying. When people get cancer, they die…” (“What the fuck,” Billi interjects.) “It’s not the cancer that kills them. It’s the fear,” her mother rationalizes. Accustomed to American attitudes toward patient autonomy and the pursuit of curative intervention at all costs, Billi cannot fathom how withholding from Nai Nai the truth of her illness and the possibility of her medical agency could constitute a “good lie.” Resolute in their belief that grief stemming from impending loss ought to be shouldered by the living rather than carried by the dying, the family outweighs Billi. As Lulu Wang put it in a Slate magazine interview, like the “uncle with his probiotics or [the] family with prayer,” the “protective power of the lie itself” is akin to other forms of hopeful palliation.

The Farewell gets at the heart of the twinned meanings of “health” both as intimate conditions which shape our personal embodiment and as a shared quality of communal life. Billi’s uncle Haibin explains, “In America, you think one’s life belong to oneself. In the East, your life is part of a whole.” The film does not shy away from showcasing the merits and drawbacks of each of these positions. Billi is distressed that Nai Nai will not get to say goodbye the way she might have liked to; her family insists that she will live longer and more blissfully if unburdened by the knowledge of her cancer. Depicting where cultural philosophies toward medical care and social responsibility diverge, the film welcomes the pain, dissatisfaction, and messiness of holding these stances together under one roof, as Billi and her relatives do.

By adopting the emotional burden and shared decision-making tasks of Nai Nai’s illness, the family displaces some of the negative affect and hardship of the experience of dying. For example, when they all go to visit a cemetery and commune with Nai Nai’s deceased husband, offering gifts at the foot of his tombstone and verbalizing happy memories, the script remarks that despite “wailing in the distance, the setting feels more picnic than graveyard.” Scholar of Asian American writing James Kyung-Jin lee argues that indeed, grief should not be the only emotion we map onto sickness and disability. He suggests we look to “those who have dwelled a bit longer in living differential futures than most of us have, those who have developed through their pedagogies of illness a version of sick Asian Americans that doesn’t equate (only) with despair and loss or, at least, holds these two feelings among a plenitude of affect” (Lee 166). Though The Farewell reflects both Asian and Asian American illness mentalities, Lee’s prioritization of disabled, elderly, and/or racialized perspectives in reckoning with a greater range of emotional relationships toward unwellness and death is mirrored in the movie.

Later, when Billi and her father, Haiyan, are directed to select a calming treatment package at a massage parlor before the sham wedding, Haiyan “contemplates this decision carefully, as if the right treatment might cure his grief. In the background,” the script notes, “someone says ‘a little pain is normal. Otherwise, it doesn’t work. Just relax.’” Against the haunting reality of terminal disease, the ability of Nai Nai and her family to relish group activities like picnicking is made possible by redistributing the “normal” pain of collective mourning into the “normal” pain of a secret sorrow. In order for the family’s lie to heal them (if not Nai Nai), it must encompass a little discomfort, like the sting of a hot rock or the pinch of an acupuncture needle.

Disability scholar and activist Eli Clare similarly frames cure as ideologically tethered to harm. In his work theorizing his frustration toward the notion of medical intervention for a body which was never nondisabled, Clare remarks that “restoration requires digging into the past, stretching toward the future, working hard in the present. And the end results rarely, if ever match the original state” (Clare 14). Via the cultural mandate that a person’s sick or disabled body ought to be disciplined back toward its former state of health, cure, in Clare’s estimation, can result in more damage than good. The characters in The Farewell effectively showcase this argument. Rather than locate the source of the family’s distress squarely within the cancerous turn in Nai Nai’s body and pursue agonizing, time-consuming treatment that can never completely restore her to youth and health, the family rejects the pressure to recuperate an able-bodied Nai Nai or exert effort toward futile medical services. Instead, after a full and poignant plotline of debate, they embrace the fact of her illness and accompany her toward death.

In Chinese characters, Lulu Wang’s dramady is called 别告诉她, which translates to “Do not tell her.” With dual titles reflective of the clash between Billi’s American sentimentality and the family’s insistence upon hiding Nai Nai’s decline from her, The Farewell raises productive questions about the ethics of familial involvement in patient autonomy, the heartache of loving someone fiercely through cancer, the humor and struggle of cultural difference, and the power of narrative for exploring our ranging relationships to the individuality and communality of health (Thai et al., Iwai). James Kyung-Jin Lee’s provocative question, “What is worth giving to imagine [a world] for sick people everywhere, and what is worth giving up,” also gestures mutually toward the value of deep sacrifice and of storytelling that opens up circumstances for our reconsideration of the omnipresence of illness in human life.

As for Nai Nai, she endures on a chipper note, espousing a cheerfulness that marks her family members’ commitment to optimism as her own ilk. She coaches Billi: “Child, I’ve walked the path of life and I have a piece of advice for you. Whatever you encounter in life, you must fight to stay positive.” Presumably, this is why Nai Nai has lived such a long and satisfied existence. Billi asks, “Are you really okay, Nai Nai?” With a twinkle in her eye, Nai Nai replies: “Yes! Why would I lie to you?”

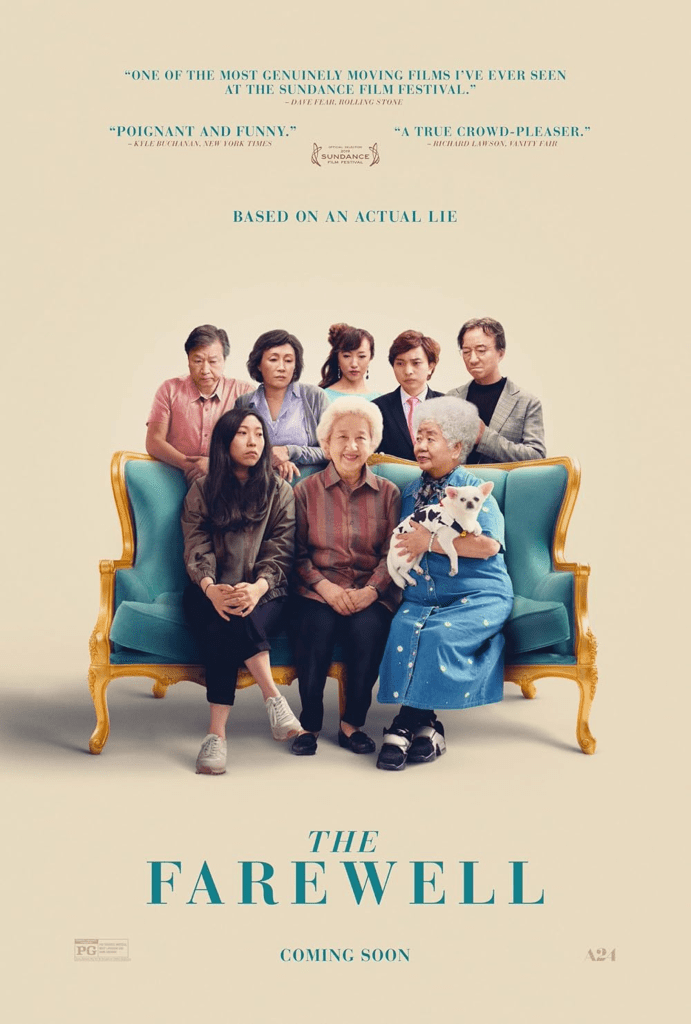

Image Credits:

Stills from The Farewell. Directed by Lulu Wang, © A24, 2019.

Movie poster of The Farewell from https://a24films.com/films/the-farewell.

Works Cited:

Clare, Eli. Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure. Duke UP, 2017.

Iwai, Yoshiko. “The Farewell: On Cultural Differences in Death and Narrative Control.” Scientific American Opinion, February 27, 2020, https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/voices/the-farewell-on-cultural-differences-in-death-and-narrative-control/.

Kang, Inkoo. “The Farewell Director Lulu Wang on Why She Stuck So Close to Her Real-Life Life,” Slate, July 2019, https://slate.com/culture/2019/07/the-farewell-director-lulu-wang-interview.html?pay=1762816536308&support_journalism=please.

Lee, James Kyung-Jin. Pedagogies of Woundedness: Illness, Memoir, and the Ends of the Model Minority. Temple UP, 2021.

Thai, Jessica, Steven Sust, and Mang-tak Kwok. “The Farewell,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 524-527, 2021.

Wang, Lulu. The Farewell. A24, 2019.