(Museum of Health Care at Kingston In-Person Doors Open Kingston)

I recall teaching Children’s Literature at Queen’s University when a student cross-referenced a scene from Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg with Victorian-era morphine bottles. Students encountered the morphine bottle during a live, in-class presentation led by the Museum of Healthcare in Kingston, Ontario. As we were still in the cautionary phase of the early post-pandemic period in Fall 2023, rather than visiting the museum, staff brought artifacts into the classroom for demonstration. The memory of this moment, when physical distancing remained paramount, seemingly mirrored the conceptual distance embedded in the student’s cross-referencing. While connecting a representational imagined space with a historical artifact may have been the pedagogical intent, I am now compelled to consider how this encounter functioned instead as a relational proposition: a moment of practice in spatial recognition between the imagined and the lived.

This experiential moment of interacting with the artifacts was closely linked to the design of the syllabus, which invited students to encounter historical narratives as embodied moments. By engaging materially with objects associated with medical intervention and childhood mortality, students were prompted to apprehend history not as abstract knowledge, but as something that had once acted upon a child’s body. This mode of engagement foregrounded both the fragility of the child, understood through bodily vulnerability and historical constraint, and the question of agency as something negotiated within, rather than outside of, those conditions. The child, as such, remained the central focus of our Children’s Literature course. One intent of this pedagogical immersion was to co-create transformative encounters in which imagined spaces could interact with lived ones, while foregrounding the child as a living agent rather than a symbolic abstraction. A fundamental question guiding the course was how to envision the child in relation to their physical vulnerability and limited capacity to navigate the adult world. While the literary texts engaged imagined spaces through the child as a living organism, I sought a way to disrupt the tacit fictional contract that confines a child’s spatial experience solely to imagination. My pedagogical aim was to create conditions through which the child could be understood in terms of bodily autonomy, beyond the cultural and social controls imposed by adult frameworks. It was in this context that the student’s connection between the historical morphine bottle and the glass vials held by Oshii’s child extended and ultimately unsettled the adult-defined parameters of who counts as a child.

This exchange compelled me to consider how spatial empathy emerges through the interpretive relationship between lived and imagined experience. Drawing on what Siobhán Wittig McPhee, Phoebe Telfar, and Leilani Forby describe as spatial empathy, understood as an “embodied understanding” of space shaped by “sensory and relational experiences,” I am particularly interested in how this concept extends to imagined spatial embodiment through mediated encounters with artifacts (McPhee et al.). Therefore, this essay examines the transformative implications of spatial empathy when a historically imbued artifact recalibrates literary images through embodied engagement, as localized in Oshii’s child. The central question that emerges is how the relational association between space and body enables empathetic immersion when historical artifacts recalibrate literary images of the child.

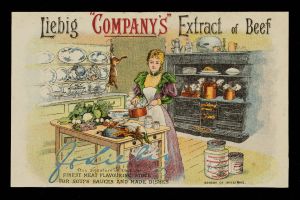

Within this pedagogical framework, the material objects introduced during the museum presentation became central sites of interpretive encounter. Among the artifacts were glass bottles used to administer morphine to children during the Victorian era in an effort to keep them calm. These “soothing syrups,” intended to dull the senses of infants, often contained harmful opioids. Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, for example, was widely used in Quebec from 1849 to 1930 and was known to contain morphine sulphate among other substances (Obladen). Following this sensory exposure to glass vials historically associated with infant mortality, the class turned to a discussion of Oshii’s post-apocalyptic surreal animation, Angel’s Egg, in which a young girl traverses a desolate landscape while protecting an egg nearly half her size. In one scene, the nameless girl pauses to observe and admire glass vials and orbs arranged in a dusty shop. During our class discussion, one student connected these glass orbs to the morphine bottles, noting how a child might innocently marvel at the fragility of a glass container that nonetheless holds ominous and potentially lethal implications.

It was in this moment of student-led connection, linking the historical morphine bottle to the imagined glass orbs in Oshii’s Angel’s Egg, that the limits of a purely analytical reading became apparent. While the student’s analysis may be read as sustaining a supernumerary association between fact and fiction, what remains most salient for me is the quieter relational process taking shape through spatial empathy. McPhee et al. identify a central pedagogical challenge in asking “[h]ow to help students develop deep connections with place when physical presence isn’t always possible or sufficient,” a question that demands approaches grounded in spatial empathy and extending beyond conventional modes of presence (13). At the heart of this challenge is an understanding of space as an embodied arrangement, one that foregrounds forms of empathetic engagement not dependent on direct lived experience to be deemed meaningful. In the case of Angel’s Egg, a forlorn child depicted within a vast, empty space gently holds a glass vial, using it to contain water, an image that activates memories already embedded within the student’s lived reality. Engaging multiple sensory registers, the scene tells a story that resonates with the student’s physical world. Whether through touch, sound, sight, or even imagined olfactory association, the glass orb cradled by the child becomes an exercise in spatial memory, recalling for many the fragility of childhood objects perpetually on the brink of collapse.

However, for the students, the metaphoric link is extended through the morphine bottle as a historical artifact, one that contains time-lapsed traces of a child’s mortality. When students interacted with these objects, the vials were no longer simply fragile containers; they became material indices of infant mortality, holding substances intentionally administered to produce a desired effect by inhibiting a child’s natural bodily functions. In this way, the vial exceeded its imagined association with harmless childhood play. Instead, the connection between the artifact and the student reconfigured the imagined through historical consequence. The significance of this relational shift becomes clearer in Aybars Aşçı’s discussion of Richard Manzotti’s claim that a museum is distinguished as a “special space” not by what objects it houses, but by how visitors connect to them. Grounded in principles of spatial empathy, Aşçı reflects on how the relationship between space and individual is shaped by the empathetic associations that generate connection (16). Here, the imagined plays a pivotal role, not as fiction, but as a mediating force that determines how historical artifacts are affectively and ethically encountered.

Reflecting on the connection my student made, I find myself similarly drawing on artifacts of memory while engaging the process of imagination. This act of recall is not abstract, but spatially situated—anchored in the classroom where the artifact was encountered, mediated by the physical presence of the morphine vial, and oriented toward the imagined space of Angel’s Egg that the student invoked. The connection proposed by the student cannot be recalled word by word; instead, it persists as an impression shaped by how these spaces were brought into relation through sensory engagement and embodied attention. It is here that the extent of spatial empathy becomes apparent, not as a complete recovery of experience, but as a recognition of how embodied understandings of space are reactivated and extended through imagination across temporal and material distance. This reflective process acknowledges both the generative capacity of spatial empathy and its limits, foregrounding what can and cannot be known experientially when meaning is produced through movement between lived, remembered, and imagined spaces.

Therefore, the vial and Oshii’s child are engaged in a conversation that is best interpreted through the framework of spatial empathy. When these two positions are brought into relation, they reveal the ethical challenge of understanding space as an embodied condition rather than a neutral backdrop. While the morphine bottle may be interpreted as a historical object that no longer poses an immediate threat to a child’s health, it nevertheless carries the material trace of Victorian socio-cultural practices that sanctioned the denial of a child’s agency through medical intervention. When this artifact is superimposed upon Oshii’s imagined child holding a glass vial, the empathetic extension between the two does not emerge automatically; rather, it depends on the student’s effort to recognize agency where it has historically been constrained. In this sense, the encounter is not merely symbolic but meta-cognitive, requiring the student to negotiate between the absent child whose body was subjected to medical authority and the imagined child who appears to exercise care and intention through play. This relational tension compels a re-evaluation of what constitutes a child’s agency, not as an abstract attribute, but as a fragile, situated capacity shaped by historical, spatial, and embodied conditions.

The intent of this essay has been to examine how spatial empathy exposes the ethical and epistemic disconnect between lived and imagined worlds, and what becomes possible when that distance is neither ignored nor resolved. Tracing agency across the figure of the child subjected to the historical violence of the morphine vial and the imagined child rendered through dystopian sensory narration requires a meta-cognitive mode of engagement that may initially appear counterintuitive. Yet it is precisely through spatial empathy that such connections become ethically legible, enabling forms of understanding that do not rely on direct experience or narrative equivalence. By holding historical harm and imagined vulnerability in relational proximity, spatial empathy makes it possible to imagine what cannot be fully known, without appropriating or aestheticizing it. In this way, the juxtaposition of the historical and the imagined does not collapse distance but creates a necessary space for ethical practice, one that allows engagement with lives, spaces, and forms of agency beyond the limits of immediate experience.

Works Cited

Aşçı, Aybars. Designing for Empathy: The Architecture of Connections in Learning Environments. ORO Editions, 2024.

McPhee, Siobhán Wittig, et al. “Decoding Spatial Empathy: Using Digital Storytelling to Overcome Barriers in Geographic Understanding.” Transformative Dialogues: Teaching and Learning Journal, vol. 18, no. 3, Fall 2025, pp. 12–32, https://doi.org/10.59236/td2025vol18iss3191.

Museum of Health Care at Kingston In-Person Doors Open Kingston. https://www.doorsopenontario.on.ca/kingston-1/museum-of-health-care-at-kingston.

Obladen, Michael. “Lethal Lullabies: A History of Opium Use in Infants.” Journal of Human Lactation, vol. 32, no. 1, 2015, pp. 75–85, https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415594615.

Rathke, E. “The Opaque Masterpiece: Angel’s Egg.” Anime Herald, Sept. 2022, https://www.animeherald.com/2022/09/03/the-opaque-masterpiece-angels-egg/.