Sneha Mantri //

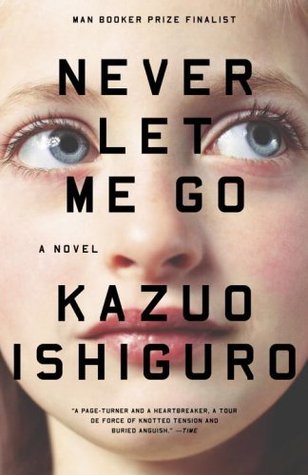

This is the first in a three-part series examining the “usefulness” of creativity through the lens of Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2005 novel Never Let Me Go. Watch for Parts II and III later this spring.

In Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro constructs a chilling alter world, in which individuals are cloned to supply organs for shadowy recipients. Throughout the novel, however, references are made not to scientific or ethical issues but to artistic creation. Ishiguro repeatedly links art to the donation process, a connection made explicit when Tommy and Kathy confront Miss Emily about her reasons for requiring the students to submit their artwork to the Gallery. Never Let Me Go asks and attempts to answer a fundamental question about the power of art to generate empathy and save lives.

From the very beginning of the novel, Kathy describes the important place that “creativity” (Ishiguro 22) held at Hailsham. Painting, in particular, seems to be the cornerstone of the Hailsham curriculum; one student “went right off poems when she started her paintings” (Ishiguro 18). Tommy is mercilessly teased because of a poorly executed painting, “exactly the sort of picture a kid three years younger might have done” (Ishiguro 19). Tommy’s inability to keep up with his peers—“he was panicked at being left behind” (Ishiguro 9), both in a rugby game and in an art class—leads to uncontrollable rage, which ends only after Miss Lucy tells him that it was “perfectly all right” if Tommy “didn’t want to be creative” (Ishiguro 23). Kathy dismisses Miss Lucy’s opinion as “rubbish” and “stupid games” (Ishiguro 24), further highlighting the central importance that art and creativity play in the lives of students at Hailsham.

One of the reasons why art is so important to Hailsham students, Kathy reveals, is quarterly Exchanges. The students are paid in Exchange Tokens for the work they submit and use their Tokens buy “private treasures” (Ishiguro 16)—that is, the work of other students. Thus, the Exchanges inure the students to giving up their work and taking the work of others. Moreover, the Exchanges, held “four times a year” (Ishiguro 16), foreshadow the four organ donations that each of the students will eventually make. The link between art and donation is repeatedly reinforced. Kathy senses this connection very early in the novel, when she asks, “What’s [the donation process] got to do with [Tommy’s] being creative?” (Ishiguro 30). Although she senses the connection between donation and art, she cannot yet articulate the sinister nature of that link.

In the absence of an official answer, the students devise a complex mythology about donation and art, centered on Madame’s Gallery. Kathy recalls that she “must by [age five or six] have already known about the Gallery” (Ishiguro 31). Because Kathy’s knowledge of the Gallery seems to be without beginning, the Gallery takes on a mythical quality to both readers and students, who nevertheless remain unsure of its purpose. Eventually, the students decide that the Gallery exists to “prove [two students] were properly in love” (Ishiguro 53) and thus obtain a deferral of their donations. The fact that Madame, rather than the students, is the one to “decide…what’s a good match and what’s just a stupid crush” (Ishiguro 176) mirrors the students’ submission of their artwork to the guardians in exchange for Tokens. In both cases, the students cede agency, just as they will later “donate” their organs without complaint or protest. Love and art, in this view, are redemptive forces against the inevitable pain of donation.

Shameem Black takes up this issue of art as a power that saves. She asserts that the philosophy of empathy reached “new intensity in the work of the British Romantics” (Black 787). Poets such as Wordsworth and Shelley, Black argues, “embedded such ethics of empathetic imaginative projection into their defenses of aesthetic pursuits” (787). By the Victorian era, artistic interest focused on the “redemptive transfiguration of pain and suffering” (Black 787). Thus, Black demonstrates that throughout the nineteenth century, art was an entry into the soul, in both a religious and metaphysical sense, during a time of increasing scientific knowledge and specialization.

Black notes that “these ideas about positive ethical value of literary empathy continue to define the way many writers conceptualize their role in modern society” (788). Certainly, the characters of Ishiguro’s novel readily accept the connection between art and inner self. In defending the existence of Gallery, Miss Emily accidentally tells the students that their “artwork revealed [their] soul” (Ishiguro 175), and the students incorporate this idea into their mythology of artwork in the Gallery. As Tommy puts it, art is a way for Madame to judge whether or not two students “match” (Ishiguro 176) in their souls. Because the link between art and soul is so ingrained in modern society and at Hailsham, the reader, too, readily accepts Tommy’s explanation. As the novel progresses, however, Ishiguro reveals that the Gallery’s purpose is far more sinister….

Works Cited

Black, Shameem. “Ishiguro’s Inhuman Aesthetics.” Modern Fiction Studies (2009) 55.4: 785-807.

Ishiguro, Kazuo. Never Let Me Go. New York: Vintage International, 2005.