Benjamin Gagnon Chainey // “All I ask is not to have to change cell, not to have to descend into an in pace, down there where everything’s black, and thought no longer exists.”[1] These words, at once suffering and troubling, are these of the French writer Alphonse Daudet, who died of syphilis in 1897. La Doulou, a collection of fragments drawn from the intimate writings of his painful end of life, is rightly titled In the Land of Pain in Julian Barnes’ English translation. Through powerful writing and thinking defined by a kind of strength in despair, In the Land of Pain strives to feel, express, and make sense of a pain so deep that it evades both sensibility and sensation.

Towards the end of his life, Daudet is overcome by “Pain [that] finds its way everywhere, into [his] vision, [his] feelings, [his] sense of judgement; it’s an infiltration” (23). With dread, he witnesses the loss of his physical and psychic capacities, which he attempts to reclaim through words. Daily, Daudet lives under the threat of pain, at time sly and insinuating, at other times of an extreme violence, a pain that portends to reduce him to the state of a “berserk marionette.” “This is me: the one-man band of pain,” he claims as suffering assaults him (Daudet 23). Though his project is to put pain into words, Daudet warns readers, especially caregivers and witnesses to others’ pain, not to be overconfident in words’ capacity to tell suffering, as this can impede their ability to understand and relieve it. “Are words actually any use to describe what pain (or passion, for that matter) really feels like?” Daudet asks. “Words only come when everything is over, when things have calmed down. They refer only to memory, and are either powerless or untruthful” (20).

In the Land of Pain exceeds its description as a personal diary, as Daudet’s pain and loss as his body and mind decay evoke a universal kind of terror. “Dictante dolore,” or, “With pain dictating” (Daudet 26), In the Land of Pain speaks to readers from a past that is still current. It unveils a world of suffering that resonates with one of the fundamental challenges of medical practice, past and contemporary, whether that medicine seeks to heal or to accompany a patient in the final stages of life—or even, now, to assist death. One of the cornerstones of medicine, and, more broadly, of any care relationship, is to be able to tell suffering: to better read it, understand it and, ultimately, heal it or relieve it.

This is the challenge that Québec psychiatrist and poet Ouanessa Younsi takes up in her medical-literary collection of stories published in 2016, entitled Soigner, aimer (To heal, to love). She finds inspiration for her texts in a range of personal and professional experiences, from her practice as a young psychiatrist among the First Nation community in the remote city of Sept-Îles, to her shifts at the psychiatric emergency ward of Montreal hospitals. Dr. Younsi’s account “takes the gamble of a poetic prose to tell suffering, compassion.”[2] These stories question the care relationship between the doctor-caregiver and the suffering Other, whom s/he attempts to cure. Through the interplay of the languages they mobilize, Younsi’s stories shed light on the epistemic tensions between medical discourse, on the one hand, and, on the other, the nuances and paradoxes concerning pain that poetic writing uncovers. As she cares for distressed patients who suffer physically and psychically, who may be dying or even dead, Younsi delivers to us her own land of pain, and refuses to submit it to the rule of medical-scientific and technical discourse. She opens it to the intricate connection between “objective and evidence-based” knowledge and the sensitive, affective, and fuzzy dimensions of the care relationship:

At this stage of my career, I trust what is essential: caring is a variation on the verb loving. We must love our patients…. Of the psychiatrist, one expects proficiency and listening. A machine can prescribe pills better than him but cannot love better. Medicine demands techniques and bits of knowledge, but that is not enough, especially in psychiatry, where the relationship is the heart and the knot. We are still human. (Younsi 9)

This relationship, “the heart and the knot” of caring, is not limited to intersubjective relations between the caregiver and the dying, but also between their languages and silences. For there are moments when words come with difficulty, when they must be chased down, moments of deep and infiltrating pain. The effort to access the right word that would tell pain, when suffering infiltrates both body and language to incapacitate them—that effort, Daudet describes as follows:

The first moves of an illness that’s sounding me out, choosing its ground. One moment it’s my eyes; floating specks; double vision; then objects appear cut in two, the page of a book, the letters of a word only half read, sliced as if by a billhook; cut by a scimitar. I grasp at letters by their downstrokes as they rush by. (Daudet 17)

In The Land of Pain, words crisscross and collide, they desegregate, flee away from any speech that would be apt to tell pain. Pain becomes a guardian of silence, at once its consequence and its cause. It forbids patients with great suffering from coming out into the space of language, from engaging in the care relationship with the caregiver. The silence of a suffering person is an unseen resistance that technique alone cannot overcome. There are “doctors who are addicted to how: intubate, operate, dissect, remove. I only think about why,” writes Younsi (18), who tries by all means to establish a dialogue with a young suicidal patient, who remains mute as to the ills that consume him from the inside. Faced with his silence, the absence of a reason why he suffers, Younsi further explains:

Sometimes I can’t help but feel the desire to extort words from him with a suction cup. To clamp his vocal cords like one squeezes a fruit to extract their juice…. I rush on that thread that dangles out, eager to pull on it. To learn what lies at the bottom of his throat. To know the color of his bones. What dies within and the stars. (Younsi 19)

Meanwhile, Daudet reads a similar recourse to poetics as one of the sources of his dreadful pain, in “the way nurses talk: ‘That’s a lovely wound… Now this wound is really wonderful.’ You’d think they were talking about a flower” (25). Younsi tries to avoid this wrinkle in the care relationship—the humiliation of the patient in his suffering by the very effort of the caregivers to relieve it—by basing her own practice on the following notion: “Healing requires humility. The therapeutic relationship is unequal. Humility balances the relationship. Allows compassion and not pity. Reminds that the patient could be me, that I do not distinguish myself from him” (10). For, indeed, even if the care relationship may give the illusion of an airtight stability of identities, little is needed to topple them, for roles to vacillate in the fight against illness:

I try to put myself in their shoes. Feel the needle penetrate in my bottom. Haloperidol and lorazepam injecting peace into me. Oozing in my flesh. Reach my neurons. Bond to my receptors. The word “dopamine” bores me. “My” matters. My truths. My years. My choices. What is intimate: my synapses. The floor gets closers. I swallow myself. Sleep like bricks, my lungs poached by the substance. (Younsi 21)

However, not unlike the “poor night-birds, beating against the walls, blind despite their open eyes” (Daudet 16), putting oneself in the Other’s shoes poses the risk, precisely, of losing oneself as it blends with the Other. Younsi understands this risk and must scale back her compassion:

I stopped the exercise of exposing myself to the patients’ ills in imagination. To survive in the system, you must touch without going through. Otherwise, you get the injection for real. I prefer when reason just goes straight ahead. To be a mirror and an echo. An invitation to reflection. (Younsi 21)

“Touching without going through” may correspond to the caregiver’s recognition of her limited power over the Other’s language of pain, over his expressions of suffering; it corresponds to the limits of screaming and to the silence it imposes on her. For the pain that infiltrates into the body and into language can take such proportions that language cannot support it. Daudet speaks of a “me” whose body, like language, is troubled by pain, lost in the land where Younsi’s suicidal patient finds himself and cannot speak or yell: “It’s all going… Darkness is gathering me into its arms. Farewell wife, children, family, the things of my heart… Farewell me, cherished me, now so hazy, so indistinct…” (Daudet 26). How to bring about the Other’s speech, the Other who suffers so much that his pain condemns him to silence? How to respect pain’s inexpressibility, without letting “the oyster close up, sink into its incorruptible space-time, far from this hospital where it resides. Inaccessible and disengaged from the world, like a coral” (Younsi 20)? According to Younsi, the answer may be a matter of dropping the why that defines the caregiver’s I. “I decided to abandon why. To be there, simply. To listen to him stay silent” (Younsi 19).

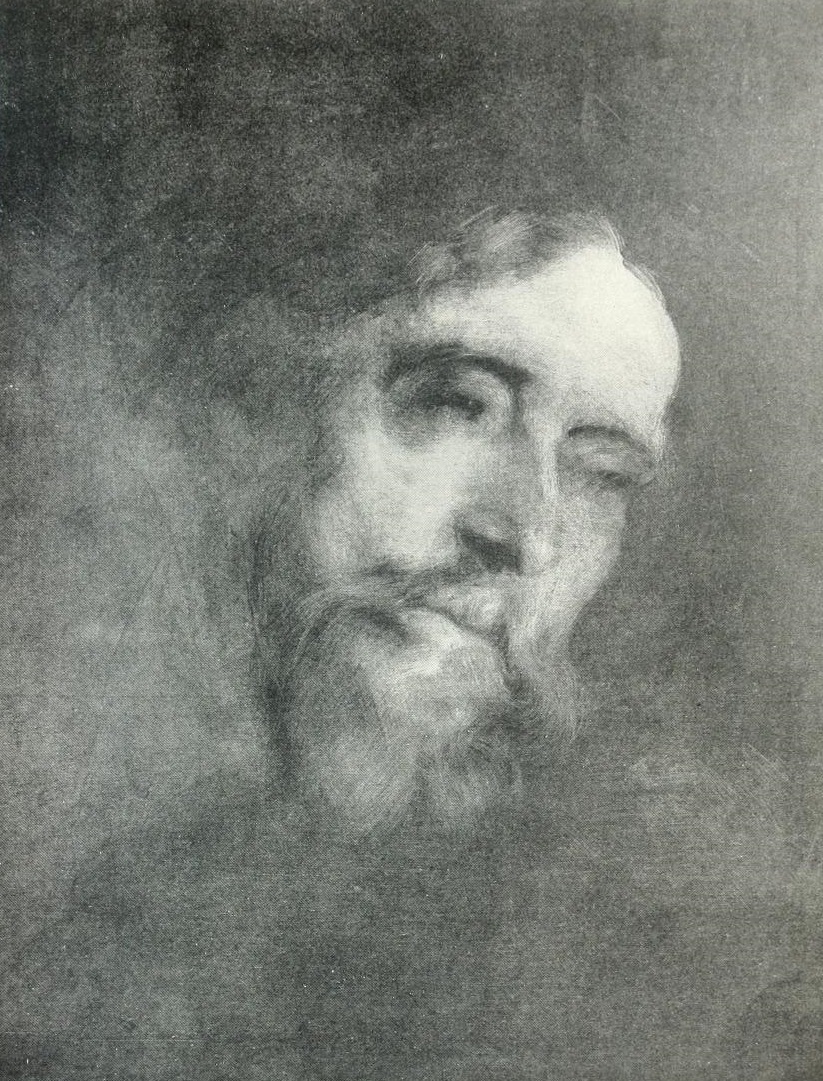

Image: Portrait of Alphonse Daudet by Eugène Carrière (no later than 1893)

[1] Alphonse Daudet. (2002). In the Land of Pain (Julian Barnes, trans.). New York, NY: Penguin / Random House. Originally published in 1930 as La Doulou (La douleur) 1887-1895.

[2] Ouanessa Younsi. 2016. Soigner, aimer. Montréal : Mémoire d’encrier. p. 9 (my translation)