Darian Goldin Stahl, Artist-in-Residence //

Lesion

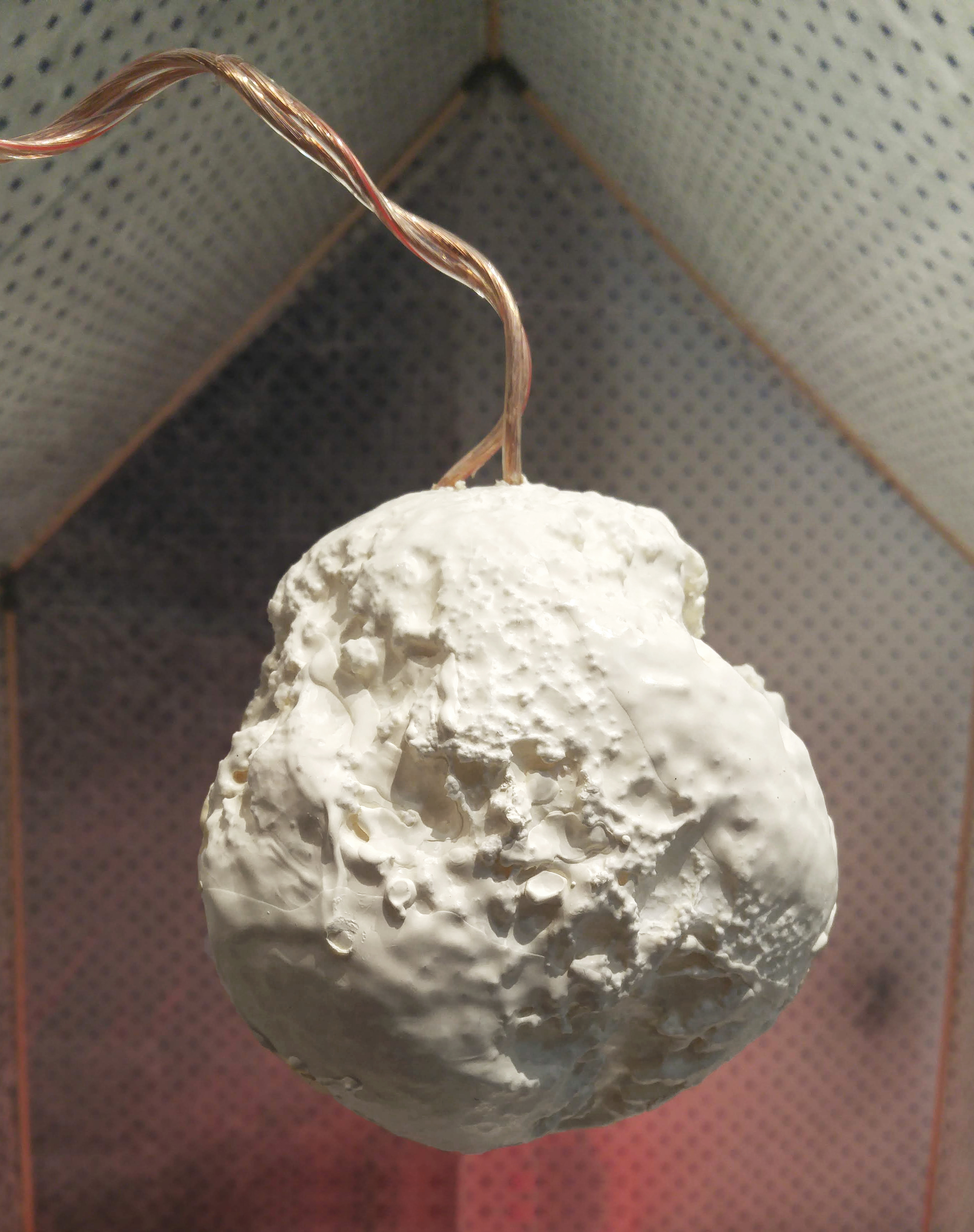

Beeswax, transducer, and sound.

2018

Lesion is a multi-sensory speculative exploration of what it would be like to materialize and hold an illness. I am most interested in discovering the community-building potential of the health humanities by transforming an internal disease into an external, tangible, and shareable fine art object that tacitly communicates the subjectivity of the patient. Through sensorial engagement with metaphorical sculpture, I aim to not only better understand a diagnosis, but to also convey the complexities and interconnections between technology and bodily knowledge in contemporary medicine.

Lesion is a participatory fine art object that engages numerous senses. Visually, this softball-sized sculpture is a malformed, milk-colored orb that appears to exist in a stasis between melting and solidifying. Drips of molten matter hang over its round form or settle into the multitude of craters and crags. The orb hangs in space by a twisted copper umbilical cord emerging from its top. This object is reminiscent of a ragged celestial body or a biological specimen imaged in a medical scan or seen through a microscope.

The sound of rhythmic, mechanical breathing fills the space around this object, which is a recording of an idling MRI machine that has been slowed down to resemble an anxious human breath. Upon closer investigation, the sound is emanating from within the orb. Viewers are invited to gently hold Lesion and discover that the object gently vibrates in synchrony with its own resonance. The breath of the orb is now a tactile sensation that imparts a sympathetic shudder up the arms of every curious caretaker.

A tension is created between this object’s grotesque form and its otherwise pleasant opportunities for engagement. Its potentially pathological appearance is mitigated by the lusciousness of its satin surface. The soft feel and uneven texture of this object combined with its stimulating reverberations create a sensual haptic experience. Additionally, as viewers hold the object and feel its “respiration,” they will also become aware of its pleasing aroma. The beeswax used to create the form exhales its sweet scent for all of those within reach. Cradling this orb close enough to exchange breaths has the dual caretaking effect of imparting each viewer with the calming natural scent of honey. By intimately joining technology and the senses, Lesion materializes the call for more embodied medical and well-being practices.

Lesion creates meaning out of illness by becoming a metaphorical proxy for the patient experience. Michel Foucault argues that metaphor has been and always will be a part of medicine, as clinicians seek to describe the space and appearance of illness through abstraction (1976, 8). For the patient, it can be nearly impossible to identify with a diagnosis without the use of a humanizing metaphor, especially when the signs of illness can only be known through bright spots in medical scans or statistics on a page. In her own experiences as a cancer patient, Jackie Stacey’s Teratologies further describes the need for metaphors to “provide the necessary balm for the psychic pain of the unbearable knowledge” (1997, 63). Metaphors are thus in the powerful position to shape the discourses of illness, particularly when they create an empathetic connection between the patient and those around her. Participatory and metaphorical objects for disease act as the intermediary stepping stone between silence and openness, stigma and acceptance, and from turning away to being with.

I believe fine art to be one of the most effective methods to create metaphor because art allows us to not only materialize the unspeakable to ourselves, but also wordlessly communicate the experience of illness to those around us. One of the aims of Lesion is to privilege non-verbal uses of metaphor that enable tacit learning and a multiplicity of meaning through sensorial engagement. This non-linguistic communication is important because, especially in moments of distress, words can be hard to find. By materializing illness through ethical artworks, difficult emotions become an object that can be seen, heard, held, inhaled, and otherwise fill the lacunae between subject and audience.

In addition to its sensorial engagement for viewers, Lesion also embodies the necessity for sensory knowledge within medicine: to understand this object’s breath more fully, one must haptically feel its form and vibration, hear its resonance, and take in its scent. Sarah Maslen, sensory studies researcher in the medical humanities, examines how expert physicians employ their senses in medicine. In critical situations, “experts tacitly respond to what they see, hear, smell and taste (though the analysis tends to lack a specifically sensory lens) rather than weighing up possible courses of action” (2016, 164). This is not to say sensory knowledge is more or less important than textbook knowledge, but that the two are intimately intertwined. Maslen warns that as medicine becomes more technologically mediated, such as the expanded use of tele-medicine, the expert body’s sensory knowledge might diminish and create a system that produces doctors who are no longer able to deftly employ their senses (2017).

Philosopher and M.D. Drew Leder also advocates for more sensory engagement in medicine. Leder’s book, The Distressed Body, concurs that the problem with data-driven medicine is that the skills of the body fall away. Sensorial knowledge can act as a crucial safeguard against error because even “quantitative data can also fall prey to problems with collecting and transporting materials, lab error, or simply individual differences and fluctuations of the body chemistry that may have no clinical significance” (2016, 104). One method Leder proposes for gaining intuitive and sensory bodily knowledge is to materialize medicine in ways that acknowledge the variations and subjectivities of patients. Partnering with our medical materials rather than substituting them for the flesh-and-blood patient can accomplish the pursuit of humanizing medicine. Lesion is an example of partnering medical technology with subjectivity, as it transforms an MRI scanner recording into an anxious breath that recalls the discomfort of the patient within the machine. Material medicine such as this gives “greater attention to the embodied experience of the patient, the physical environments in which treatment unfolds, and the material things we use as agents of healing” (2016, 74). The act of creating and sharing sensorial medical art-objects can form a community of empathetic healers in any setting where the object is passed between doctors, patients, and families.

Both medicine and art are seeking to make the invisible visible: the information of the self that can be shared and understood. Instead of only seeking to reveal the somatic, the creation of Lesion is also seeking to reveal the psychological. Lesion wordlessly communicates the duality of unease and pleasures of life after a diagnosis by presenting both anxious sounding breath and pleasant aroma. Through materializing illness into an object that engages a multitude of senses, Lesion is a sculptural manifestation for the complex entanglements of metaphor, bodily knowledge, and lived experiences of illness and well-being.

Darian is the Artist-in-Residence at Synapsis. To see more of Darian’s work, please visit her website: http://www.dariangoldinstahl.com

Works Cited:

Foucault, Michel. 1976. The Birth of the Clinic. Translated by A.M. Sheridan. London: Routledge.

Leder, Drew. 2016. The Distressed Body: Rethinking Illness, Imprisonment, and Healing. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Maslen, Sarah. 2017. “Layers of Sense: The Sensory Work of Diagnostic Sensemaking in Digital Health.” Digital Health 3: 1-9.

Maslen, Sarah. 2016. “Sensory Work of Diagnosis: A Crisis of Legitimacy.” The Senses and Society 11, no. 2: 158-176.

Stacey, Jackie. 1997. Teratologies. London: Routledge.