Alicia Andrzejewski //

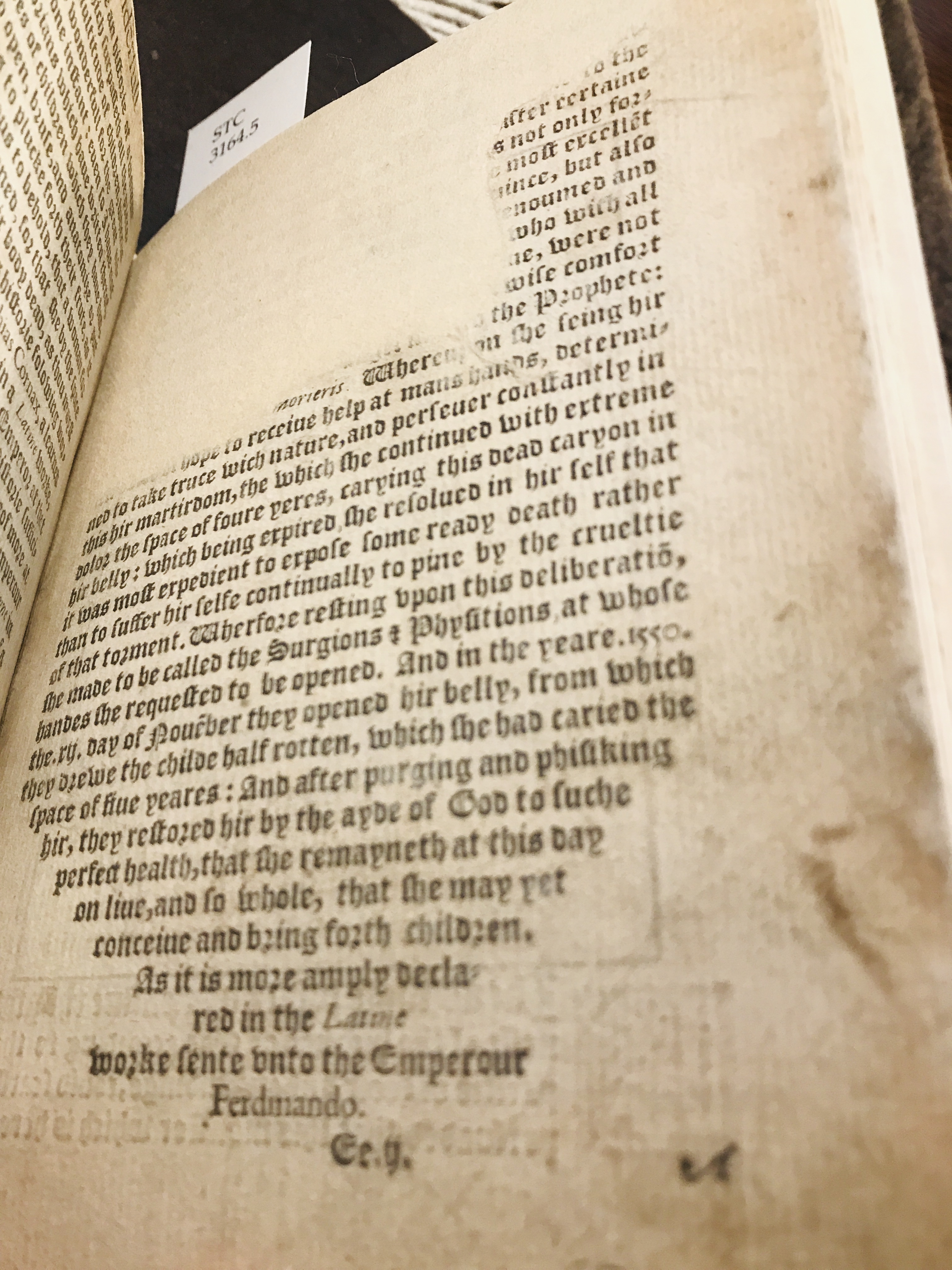

In one of my monthly visits to the Folger Shakespeare Library this year, I called up Pierre Boaistuau’s Certaine secrete wonders of nature: containing a descriptio[n] of sundry strange things, seming monstrous in our eyes and iudgement, bicause we are not priuie to the reasons of them (1569). I was looking for a particular image, but found another. An image of a woman, Margreta, that opens the section, “A wonderfull historie of cetaine women which have brought forth a great number of children: And another whiche bare hir first fruite five years dead within hir belly” (108).

Margreta is the latter.

The image that opens this section emphasizes the surgeon who operates on Margreta—the woman who carried a dead child in “her belly” for five years. This surgery is the process, the “wonderful history,” this text celebrates—most central in the image and to the readers. The male surgeon in the center of the portrait is in the process of removing the last “piece” of the dead child from Margreta’s body—their head. The surgeon’s hand hovers over the dead child’s face. The other hand holds a scalpel. In the bottom right corner, a basin of body parts sits within Margreta’s view. The child’s legs and hands are visible. There are three objects on a mantle, hovering over Margreta and the surgeon. A dagger, a plate, and a pitcher. A curtain is draped in the upper left hand side, signifying a domestic scene. Margreta’s bed is ornate and a man’s head crowns the top of it—the only face in the image staring directly at viewers.

My eyes are drawn to Margreta, however, who lies contorted in bed, her breasts and belly exposed. Her eyes are cast to the right, away from the surgical process she is experiencing. Her hair falls in tangled curls around her face. Her legs fall to the side, one on top of the other. She grimaces, she grits her teeth.

This image is not described in full until the end of the section, after a description of a woman who “brought forth” five children. In 1545, Margreta felt sharp pains that suggested she was in labor and, according to Boaistuau, “her mother and other certain sage women” were called to help. Upon arrival, however, they heard a noise like a “thunder clap” within Margreta’s belly which “made them think” the child was dead—had lost its battle with “nature.”

In the Folger edition, the page blurs out here—a blank space—and the sage women disappear. The text returns with a description of Margreta’s five year “martyrdom.” After these five years, finally, “she resolved in herself that it was most expedient to expose some ready death rather than to suffer her self continually to pine by the cruelty of that torment. Wherefore resting upon this deliberation, she made to be called the Surgions and Physicians, at whose hands she requested to be opened.” In 1550, Margreta faces her fear of death, is operated on, and the baby is removed from her body. Boaistuau concludes the section by telling readers that surgeons restored Margreta to such perfect health “that she remayneth at this day…so whole, that she may yet conceive and bring forth children.”

A “resolution” still offered to people whose pregnancies end in stillbirth today.

I don’t know if Margreta exists, or how much of this story is true, but I asked a medical student why Boaistuau would’ve made such a disturbing image and case so central. He responded, “If I were writing a book about medicine, and wanted it to sell, I’d describe the most strange and fascinating cases I came across.”

Fascinating. Strange. Sell.

After a stillbirth last year, Gillian Brockell wrote an open letter to online companies who continued to advertise to her. Ads for the clothes, cribs, and other items her baby would never use flashed across her screen. Of these companies, Brockell states: “I know you knew I was pregnant,” but after returning home “with the emptiest arms in the world” they didn’t seem to know about her pregnancy’s tragic end. Brockell asks why they did not see her googling “baby not moving,” or the three days of online silence that followed. The letter ends, “Please, Tech Companies, I implore you: If you’re smart enough to realize I’m pregnant, that I’ve given birth, then surely you’re smart enough to realize my baby died, and advertise to me accordingly, or maybe just maybe, not at all.”

When reading Brockell’s devastating and brave letter, lines from Katherine Philips poem, “On the Death of my First and Dearest Child, Hector Philips, born the 23rdof April, and died the 2nd of May 1655” came to mind:

Thus whilst no eye is witness of my moan,

I grieve thy loss (ah, boy too dear to live!)

And let the unconcerned world alone,

Who neither will, nor can refreshment give.

Margreta’s story, and the “unconcerned” and unwilling world both Brockell and Philips describe, demonstrate how women’s narratives about their own bodies have been appropriated across time and put to use—yet simultaneously sidelined and ignored. It’s not that the medical industry and all of the businesses attached to it aren’t “smart enough” to recognize that pregnancy does not always end in the birth of a healthy child and / or mother—it simply does not serve their purpose, does not sell. So the pregnant person in question must grit their teeth in grief, their bodies and lives invaded by those who want to sell a particular story. One that ends in a “whole” body, a “refreshed” body, a body that can try again. These narratives of giving birth are warped, wrapped up, and then silenced because of heteronormative and patriarchal narratives that privilege the surgeon who stitches a body back together, offers the “refreshment” Philips tells us is an illusion, so that the person in question can “go on.”

The unconcerned world; the triumphant surgeon; the invasion of a grieving body and soul. I understand why, for Margreta, it took five years to offer her body up—to let go of the life that was consequently used to sell her secrets as “wonders of nature.”

Works Cited

Boaistuau, Pierre. Certaine secrete wonders of nature: containing a descriptio[n] of sundry strange things, seming monstrous in our eyes and iudgement, bicause we are not priuie to the reasons of them. Folger Shakespeare Library, STC 3164.5, 1569. http://hamnet.folger.edu/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=160934

Brockwell, Gillian [@gbrockwell]. “An open letter to @Facebook, @Twitter, @Instagramand @Experianregarding algorithms and my son’s birth.” Twitter, Dec. 11, 2018.

—. “Dear tech companies, I don’t want to see pregnancy ads after my child was stillborn.”Washington Post, Dec. 12, 2019.

Philips, Katherine. “On the Death of my First and Dearest Child, Hector Philips, born the 23rdof April, and died the 2ndof May 1655.” Early Modern Women’s Writing, editor Paul Salzman, Oxford UP, 2000, pp. 270-71.

Further Reading

Wilson, Jean. “Dead Fruit: The Commemoration of Still-Born and Unbaptized Children in Early Modern England.” Church Monuments, XVII, 2002.