Bassam Sidiki //

In the summer of 2019, a mere months before the pandemic would dramatically alter our lives, I boarded a plane from Detroit to Honolulu. I had received a pre-doctoral research grant to visit the Hawaii National Archives where they keep papers of the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement on the island of Molokai. This settlement, built to isolate mostly native Hawaiian people with leprosy —what we today call Hansen’s disease (HD)— had been in existence for about a century, built in 1866 and in operation until 1969. The colony achieved notoriety especially because of the Belgian missionary Father Damien who served the lepers there, himself succumbing to the disease and dying in 1889. The leper colony also inspired a host of literary narratives: from Jack London’s 1912 short story “Koolau the Leper,” which fictionalized the 1893 Leper War on Kaua’i, to contemporary literary and historical novels. Like many researchers, I didn’t know what I was looking for when I went to the archives. But I wanted a glimpse, however spectral and out of reach, of the lives at the center of so many of the speculative fictions I had been reading at the time. In Derrida’s words, I had been struck by a kind of archive fever, a mal d’archive.

I reserved an airbnb near the Ala Moana Center, a short distance by bus from the Archives and the tourist-filled beaches of Waikiki. My week-long trip fell toward the end of August, so the tourism was at its peak (little did I know that in a few months it would come to a total halt). I didn’t pretend to not be excited about my first time in the Pacific, so I too looked the part of the tourist; I would wear my aloha shirt and shorts to the Archives, work there from about 10 am to 4 pm, then head to Waikiki for some sun and sand. I was soon to blame that sartorial choice when I caught a terrible cold, my metaphorical archive fever turned hilariously but inconveniently literal.

I had forgotten that archives are notoriously cold places, to better preserve their delicate documents. So my first day in the building I tried my best to conceal the chattering of my teeth as I looked through folder after folder, taking pictures with my phone so I could read the documents more closely later on. I swore to dress in warmer clothes the next morning, but by the time I arrived back at my airbnb it was too late: a sneeze, then another, a sore throat. It was a cruel irony that delving into archives of sickness had made me sick too. I obviously hadn’t caught leprosy, but all the same. As I reflect back on the experience, I realize that it probably wasn’t my beach clothes that had been the culprit. Sifting through old, dusty papers, as Carolyn Steedman writes in her book Dust, may as well unleash dormant viruses and make a body already riven with archive fever all the more feverish. As I lay on the sofa-bed in the airbnb, my head and throat aching and my nose stuffy, I hoped for a speedy cure.

**

While I hoped for a cure to my own trivial cold as I conducted my research, and even as we today hope for an end to a global pandemic, the hopeful voices of the incarcerated lepers at Kalaupapa often broke through the bureaucratic correspondence of the medical officers and superintendents of the colony. One highly intriguing document, which led me down a fascinating path of discovery, not only spoke to hope but also to the way that illness often becomes a site of intense political contestation. Contrary to the well-meaning pundits today who argue that one must not make mask-wearing a political statement, what I found in the Kalaupapa archive suggests that the body, whether in sickness or in health, is often always already politicized.

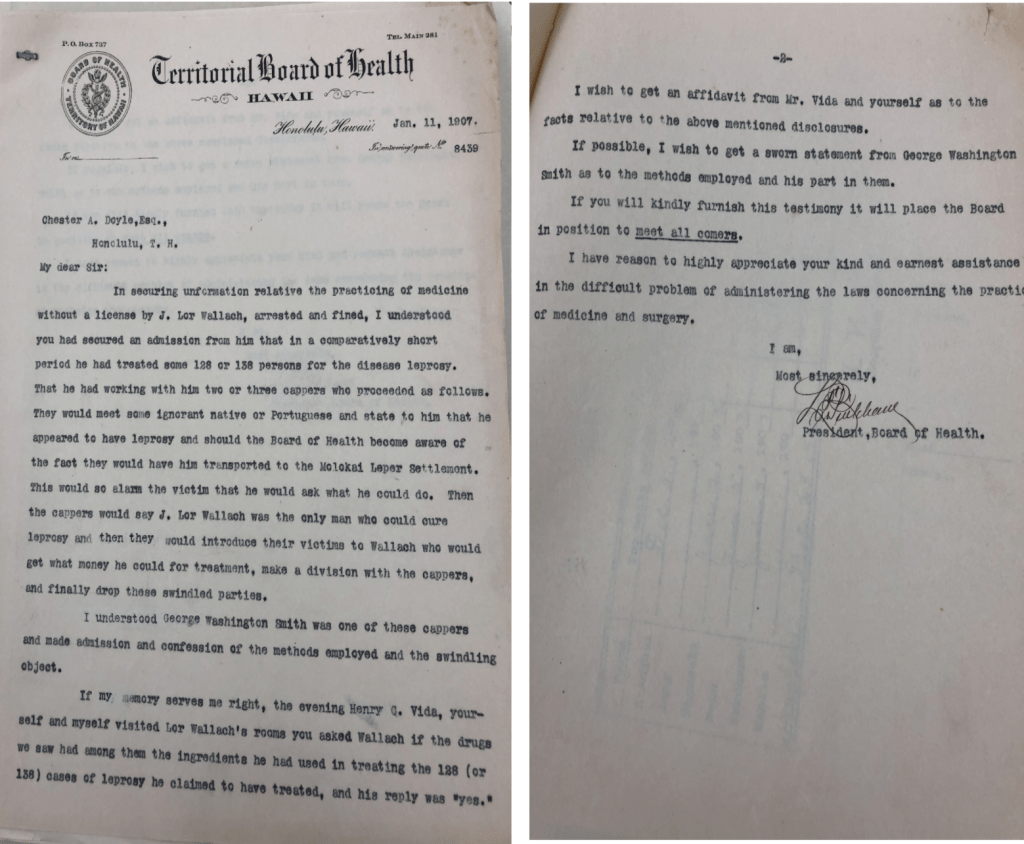

When looking back through the almost 260 photographs of documents on my Google Drive, one piqued my special interest. It was a piece of correspondence by the President of the Board of Health of Hawaii in 1907, Lucius Pinkham (Fig, 1). The letter talks about the arrest of a man named J. Lor Wallach who, according to Pinkham, had divulged the fact that he had been treating leprosy without a medical license. Moreover, Wallach used “cappers” to trap these unsuspecting people to try his remedies; the cappers would falsely attest to the effectiveness of Wallach’s medicines and coax the lepers to try them as well. I followed this lead, finding mention of Wallach in such newspapers as the Pacific Commercial Adviser, according to which Wallach had ignited a full-blown political controversy with Republican, Democrat, and Home Rule parties having vested interests.

527 lepers at the Molokai settlement had petitioned the Board of Health to let Wallach try his experimental remedies on twelve of them, despite the fact that his medical credentials were dubious at best. The logic behind their petition went as follows: “That while the hope of a cure by the treatment of J. Lor Wallach may prove only a hope, we feel we should not be deprived of that hope and that the disease with which we are afflicted should appeal to your honorable body to sustain that hope until proven or disproven.” Furthermore, the lepers were supported by Charles K. Notley, a Kanaka Maoli politician and leader of the short-lived Hawaiian Home Rule Party. There was to be a vote on whether to allow Wallach to try his “cure,” and in a tie-breaking vote Pinkham allowed him to go to Molokai. Pinkham’s speech explaining his decision, republished in the Pacific Commercial Adviser, contains allegations that Notley was merely using Wallach to incite his fellow Hawaiians to support independence from the United States (Fig. 2).

What this archival material suggests is that, while leprosy and its treatment through colonial biomedicine were used by American imperialists as pretexts for Hawaiian annexation — as scholars like Neel Ahuja have shown — they were also sites of agency for native Hawaiians striving for decolonization. In refusing to genuflect to American and European standards of the new biomedicine, which effectively distinguished “true” medicine from Wallach’s quackery, the Kanaka Maoli lepers were in fact staging a kind of double decolonization: of land and of scientific epistemology. The hope for a cure from leprosy, in this way, was also a hope for decolonization and Hawaiian independence.

**

On one of my last days in Honolulu, as I was exploring more of Waikiki, I came across a statue of Mahatma Gandhi in Kapiolani Park right across from Queens Beach (Fig. 3). While statues of Gandhi abound all over the world (with recent controversies around tearing them down because of his anti-Black views during his earlier South African phase), for some reason coming face to face with a bronze rendition of the Indian leader with palm trees in the background seemed more meaningful to me. There was obviously the connection in my mind between India’s colonial experience at the hands of the British on the one hand and Hawaii’s ongoing colonization by the United States on the other. But as I revisited the J. Lor Wallach case, the significance of Gandhi’s statue stood out in even starker relief.

One of the ways that the Board of Health of Hawaii delegitimized Wallach’s medical expertise was to paint him as a mere “fakir,” a term employed in British colonial contexts to denote a Hindu or Muslim ascetic who lives on alms, but may also refer to someone who uses alternative or religious methods of healing. Wallach claimed to have gotten his leprosy cure from India when he was a child; according to the Hilo Tribune (1907), Wallach’s cure comprised “‘moss from female rocks’ combined with ‘powdered worms’ from India and the horns of young deer.” Owing to the apparent preposterousness of such a concoction, Wallach was all around derided in the press as “Worm Wallach,” “Rock Specialist,” “quack,” “fakir,” and “faker,” the contiguity of the latter two epithets being richly suggestive (Fig. 4).

According to another newspaper, Wallach would tell people that he could not demonstrate the cure to them at that very moment because he was “awaiting ingredients” from India. I suggest that, while indicating the always already political nature of medical practice, the Wallach controversy also ties together disparate colonial contexts: American Hawaii and British India. Seeing Wallach being described as a fakir as I recalled gazing at a monument to Gandhi in Hawaii, I couldn’t help but be reminded that the Mahatma, too, was unflatteringly described this way by his arch-nemesis, Winston Churchill: “a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Viceregal palace.”

While Churchill was referring to the Middle Temple Inns of Court, he might as well have been invoking the leprous temple priest from Rudyard Kipling’s famous leper story, “The Mark of the Beast” (1890), in which a drunken Englishman named Fleete desecrates a temple to Hanuman. As revenge, the priest, also referred to as the “Silver Man,” bites Fleete and leaves the titular “mark of the beast,” sending the Englishman into rabies-like fits. Notably, the colonial doctor Dumoise’s putatively superior scientific medicine comes to no avail; the narrator and a character named Strickland severely torture the fakir into breaking the “spell” that he had cast on Fleete (Fig. 5).

“Strickland shaded his eyes with his hands for a moment and we got to work. This part is not to be printed,” the narrator of the story says just before the torture commences. Indeed, so many instances of colonial violence and anticolonial resistance have been expunged from the archive, deemed not fit to be printed. And yet, sometimes the archive can give clues to a certain insurgent impulse among the colonized — how Kanaka Maoli lepers took their “cure” into their own hands. But the branding of Wallach as a fakir has some resonance for Kipling’s story too. If “fakir” suggested that Wallach was a “faker,” in Kipling it is the fakir’s occult knowledge that holds the hope for a true cure. More importantly, the inter-imperial transfer of a term such as “fakir” in the context of the Wallach controversy shows how the validity of biomedical knowledge in the late imperial era was infused through and through with political, racial, and colonial meanings.

Note: I realize that the term “cure” is deeply controversial in contemporary disability studies, but to project that ambivalence about the word backwards to the context of the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement would be ahistorical. Even today, cure, treatment, and rehabilitation have different, sometimes liberatory, resonances in the Global South and other (post)colonial contexts. As the 527 lepers from this archive show us, for them, cure was something to be hoped for.

Cover Image: Kekauluohi Building, Hawaii National Archives, Honolulu. Photograph by author.

Acknowledgments: I’d like to thank Prof. Hadji Bakara and the graduate students in the Animating Archives seminar at University of Michigan for their feedback on this reflection.