Marcus Mosley //

According to the CDC, 1 in 2 Black/African-American gay, bisexual, same gender loving and other men who have sex with men (MSM) will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime.1 In facing such statistical odds, it is imperative that the public health community engage in messaging that not only reaches this group but is informed by the stories of Black MSM. However, Black MSM are often over-studied and over-“targeted,” leading to suspicion and skepticism; this scrutiny is layered on top of founded mistrust of the medical and public health communities, and thus the messaging that comes from them. This dynamic becomes a powerful obstacle in developing an effective public health messaging campaign that improves behaviors and outcomes and does not contribute to that historical mistrust.

Narrative medicine can provide a useful tool for engaging with Black MSM and developing effective messaging around two HIV prophylactic medications, PEP and PrEP, both of which are underutilized by Black MSM in comparison to their white counterparts.2 The three movements of the narrative medicine framework are attention, affiliation, representation.3 Here I will describe how this framework can be adopted by those in the public health community to produce more effective communication and engagement with Black MSM, and more broadly, other minoritized communities.

Attention

Attention given to the Black MSM community is necessary to understand the true barriers and obstacles to uptake PEP and PrEP. Public health initiatives and interventions geared towards this population must first invest the needed time and resources to pay attention and listen. This can take many forms (e.g. ethnographic, or community-based participatory research, such as the PhotoVoice method). If we look at one successful example, we see how researchers in California used the PhotoVoice method to examine the sexual health issues of non-gay identified African-American MSM.4 Participants were instructed to take photos of their everyday life experiences, paying specific attention to the context of HIV infection and possible prevention. After taking photographs, participants described their photos and had a discussion. One participant took a picture of Mosswood Park and noted that despite the hospital being across the street, it was a “dangerous place” and “cruising area.”4 Locating sites of infection allows researchers and community members to target their advocacy. This is one example of how qualitative methods, in particular, can be used to pay attention and simultaneously empower a “targeted” community with co-ownership of the research process. Truly, listening to the narratives of those in the community and providing recognition, may not only lead to better affiliation but may also provide access to unforeseen psycho-social and structural inputs that are influencing sexual practices and behavior and orientations to medication use, such as PrEP or ART (antiretroviral therapy).

Affiliation

Developing an affiliation with the community can only come after proper attention. Affiliation can be developed by having members of such groups, especially respected community members, lead the research process from the beginning. Yet, African Americans are underrepresented as HIV researchers;5 directing research funds towards minority-serving institutions and requiring that new studies be co-led by members of the community – or in research speak “key population” – of focus could potentially increase the number of grant-funded African-American HIV researchers while improving affiliation with the Black MSM community. During the course of developing interventions, mistakes are bound to happen, and desired outcomes are not always achieved. However, having a strong affiliation suggests trustworthiness and can keep the lines of communication open between researchers and communities. There is a cooperative relationship between affiliation and representation. The better the representation, the better the affiliation and vice versa.

Narrative Medicine advocates for using methods of qualitative research to develop better affinity with marginalized communities because qualitative researchers can serve as “‘ethnographic witness[es]’ to the exclusions that are the enabling material conditions of elite institutional privilege and ethical indifference.”3 In other words, qualitative methods if conducted from the position as an ethnographic witness, as opposed to a researcher, have the possibility of allowing one to listen better to a community compared to other research methods due to having access to private, personal and on-the-ground experiences. This intimate perspective leads to better representation, which serves as evidence of proper affiliation. Charon et al., in The Principles of Narrative Medicine, write: “The practitioner of qualitative methods also constructs affiliation, not only by establishing rapport for entering those other spaces but also building a form of care-laden solidarity by getting the research subject’s life, work, challenges, loves, and social sufferings ‘right,’ such that when presented with the drafts of a write-up she can recognize herself and her words in these distillations of a whole way of life.”3

Representation

Ethical and responsible representation of marginalized communities in public health messaging around PEP and PrEP is imperative as it can influence levels of awareness and thus uptake. Conversely, poor representation and messaging can contribute to stigma and shame. Poor representation can result from poor attention and affiliation. Consider the Swallow This advertisement (Fig. 1), produced by Harlem United with Better World Advertising (BWA). It shows the image of a blue PrEP pill sitting on a stuck-out tongue of a Black man. This graphic employs the elements of synecdoche, a figure of speech in which a part is made to represent the whole or vice versa.

The intended viewers and “target” of the ad, Black MSM, are able to see and recognize themselves in the ad. However, this possible recognition comes alongside racist reductive norms. The powerful subversive aspect of this image is that it can be any Black individual due to the lack of facial features and anonymity. An open mouth is the first thing one notices when looking at this visual. Yet, here, Black MSM are reduced to mouths — sexual objects. The command, SWALLOW THIS, is so jarring because of the sexual innuendo, which is meant to be sexy. The imperative verb in the phrase, “Swallow This,” creates a sense of infantilization of Black MSM, similar to two-word phrases like: “sit down,” “go catch,” and “roll over,” used with a dog. The capitalization, of the entire phrase, creates a shouting effect for the reader, rendering a sense of urgency, panic and fear. This “call to action” is a command, authoritative and, thus, implying that the subject of the voice, from the image of the Black body, does not belong to an autonomous member of the “target” audience – Black MSM.

Similar to “scopophilia,” the pleasure of looking, being used as a “methodology of persuasion” in print advertisements of psychotropic medications6 — here too, an active/passive relationship is being established to try to persuade. The subjugation and the objectification of Blacks are reinforced by the command. In the evolution of print advertisements for psychotropic drugs, images of medication soon replaced the doctor in the ads. The new appearance of medication in the images “indicated that the process of alleviating and ablating symptoms took place outside the office altogether.”6 Furthermore, “the progress of medications came to symbolize a discipline of the mind. As extensions of the medical establishment, pills brought a form of obedient control.”6 The Black mouth in the ad is consuming the pill (standing in for the doctor/medical institution), providing a sense of agency. However, it is not a free-willed consumption but a commanded one, similar to psychiatric direct observed therapy, and is in the context of being viewed as a sexual object that also swallows other things.

The problem with the disciplined body, “of obedient control,” is that it leads to disembodiment or disassociation from the self; “the disciplined body becomes monadic.”7 This disembodiment is dehumanizing and reflected in the ad by the lack of any facial features or eyes. It is monadic; the image does not show any relationality with any other bodies. For example, the PrEP ad does not show a couple; the association is between a Black mouth and a blue pill.

This advertisement is a single example of problematic representation where the public health community’s anxiety around an increasing HIV incidence among Black MSM is palpable and reflected in public messaging for that group, who are often viewed as “non-adherent patients.” Perhaps, it is that bias that resulted in the shouting command, reflecting the goal for the public-health community that Black bodies become ‘disciplined,’ as PrEP needs to be taken every single day. Not only does the public health community want Black bodies to be “disciplined bodies,” they imagine that is the narrative Black MSM will respond to and thus desire to adopt.

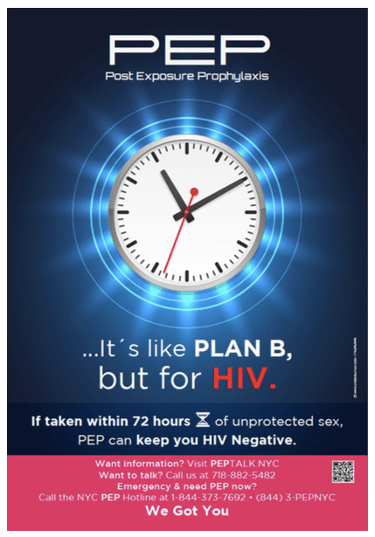

Often, public health messages, like Swallow This, are geared to shock the key population into action. When surveyed by BWA, the majority of respondents agreed Swallow This was convincing and memorable; yet, only 12% of respondents reported initiating PrEP use. However, prioritizing shock and memorability can be stigmatizing and reflect a lack of attention and affiliation. In developing a public health messaging for PEP, using a community-based participatory method with Black MSM, my colleagues and I found that using the word “exposure” (a clinical term that has connotations of urgency) to convey situations where PEP would be needed produced feelings of anxiety and fear;8 participants also believed photos of Black men in the adverts contributed to feelings of mistrust.8 This knowledge produced from affiliation and attention to the community allowed us to produce an effective public health campaign. We designed an advert that did not include images of Black men and one that still communicated the sense of urgency and time-dependent nature of PEP through the use of an analog clock, a sand clock timer, and an analogy to Plan B (See Fig. 2); this proved to be non-stigmatizing and effective in increasing PEP demand.8

Those in the public health field often assume that Black bodies have a limited sense of agency due to overpowering inequities and systemic forces. The majority of HIV prevention, therefore, seeks to develop interventions where Black MSM can “regain” a sense of control, reflecting the central role of discipline in prevention. More often, public health campaigns represent Black MSM as objects that need to be controlled. Better understanding the history and experiences of sexual objectification of Black men as well as acknowledging that Black men do have agency can lead to more humane advertisements and better prevention strategies. Adopting the narrative medicine framework of attention, affiliation and representation can hopefully lead to improved outcomes and health for the Black MSM community.

Author Bio: Marcus Mosley is a 4th-year medical student at The City University of New York (CUNY) School of Medicine. He has a master’s in narrative medicine from Columbia University.

Cover Image Source: The face of a black man with his hand on his cheek representing a man worried about HIV; a poster from the America responds to Aids advertising campaign. Lithograph, 1993. [Washington (D.C.)] : Department of Health and Human Services, 1993 (U.S.A. : U.S. Government Printing Office).