The Communication of Pain

In her book The Body in Pain, Scarry discusses the way that pain “shatters language” and threatens to be “unsharable” (4,5). She describes how pain belongs to an internal geography,

when one hears about another person’s physical pain, the events happening within the interior of that person’s body may seem to have the remote character of some deep subterranean fact, belonging to an invisible geography that, however pretentious karma has no reality because it has not yet manifested itself on the visible surface of the earth. (Scarry 3)

This is the challenge of the clinical conversation, to translate an internal experience or symptom, such as pain, to the external world. While physicians are trained in a medical language that provides a specific way of talking about the body and symptoms, patients aren’t. Instead, patients use story and description, if they can, to try and relay what they are experiencing. Yet, physicians typically aren’t explicitly trained in the art of interpretation. Occasionally, this difference in language can lead to a disconnect between patients and practitioners.

As a geographer, I am curious about the ways that the geographic self, which prioritizes the spatiality of the body, might help us think differently, understand more deeply, and ultimately recognize better the communication of pain.

What is the Geographic Self?

Within geography, there is growing scholarship on the geographic self. While there are many different uses of this concept, I am interested in how it can be used to think differently about the body itself, primarily how it frames the body as home for the self.

To think of the body as home, it first needs to be seen as a space where the self exists. In their work, Butler and Parr “use the term ‘body space’ to refer to the physical, biochemical spaces of the body itself” (13). Simply put, we live within our bodies, we are embodied beings so the self or the mind exists within the body. However, this is not a space devoid of meaning, in fact it is the primary place where we live.

In Places through the Body, Nast and Pile discuss this space as a “spatial home” when they map out how each “individual is located in a body and that being in a body is also about being in a place” (1). The geographic self emphasizes embodiment as a self residing within the body, re-contextualizing this space within the body as the most important place, the spatial home for the self. This is the most intimate home that we experience. It is in this place that the mind and body are connected, that this embodied relationship is established.

This geographic framing of the body complicates the idea of what it means to relay pain to another person. It is more than a challenge of language; it is about rendering visible the internal experiences which as Scarry suggests, “has no reality because it has not yet manifested itself on the visible surface of the earth” (3). The job of the patient is to somehow manifest their pain so that it is visible to the practitioner. How might this understanding of the process of relaying pain change how we interpret the words of those trying to do just that?

Pain Disrupts

I argue that the geographic self as a way of conceptualizing the body, has the potential to be a useful tool in interpretations of pain descriptions between patient and doctor because it illuminates how to recognize when patients are describing significant pain moments that should be taken as valid.

In the clinical space a doctor asks the patient, on a scale of 1 to 10 what is your pain level? Then, maybe they follow up with asking the patient if they would describe their pain as burning, stabbing, aching or any number of other descriptive terms. However, when we look at how patients try to narrate these experiences, in conversation, or in patient narratives, they may or may not use this language to describe their pain experience.

For example, in her patient narrative, Emma Bolden describes the things her body does as though it is something other than herself,

There I am, the person I cannot remember as a person, the person detached from her being, from her body, who no longer lived inside of a story she could understand”. (65)

The impact of her pain is such that it disrupts her mind/body relationship so that she no longer feels a sense of belonging with this body, even as she lives within it. Pain, through this geographic lens becomes a disruption of this mind/body relationship. It is from this realization we can begin to recognize statements such as Bolden’s as statements of significant, valid pain.

Her pain has gotten to the level that she feels a degree of separation from her own body, for the physician looking through the geographic self, this is a signifier of immense pain. This is a 10. This is valid. This is pain.

I posit this theoretical framing of the geographic self as a way to shift thinking about the body, as a lens through which not only literary or analytical analysis can be conducted but as a very real tool to facilitate a way of interpreting the language of the patient and their pain.

Works Cited:

Bolden, Emma. The Tiger and the Cage: A Memoir of a Body in Crisis. Soft Skull Press, 2022.

Butler, Ruth, and Hester Parr, editors. Mind and Body Spaces: Geographies of Illness, Impairment, and Disability. Routledge, 1999.

Nast, Heidi J., and Steve Pile, editors. Places through the Body. Routledge, 1998.

Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford University Press, USA, 1985.

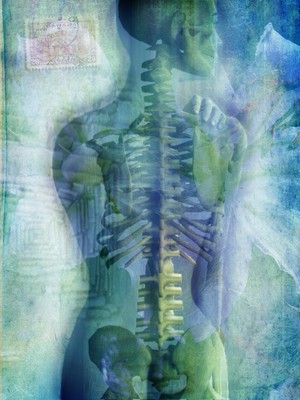

Image Credit:

Back pain. Bill McConkey. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Source: Wellcome Collection.