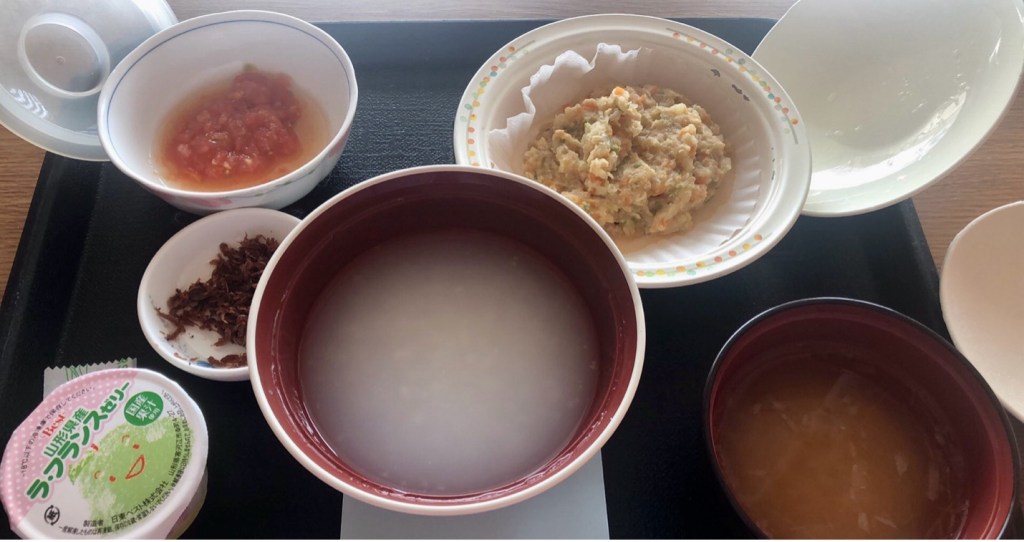

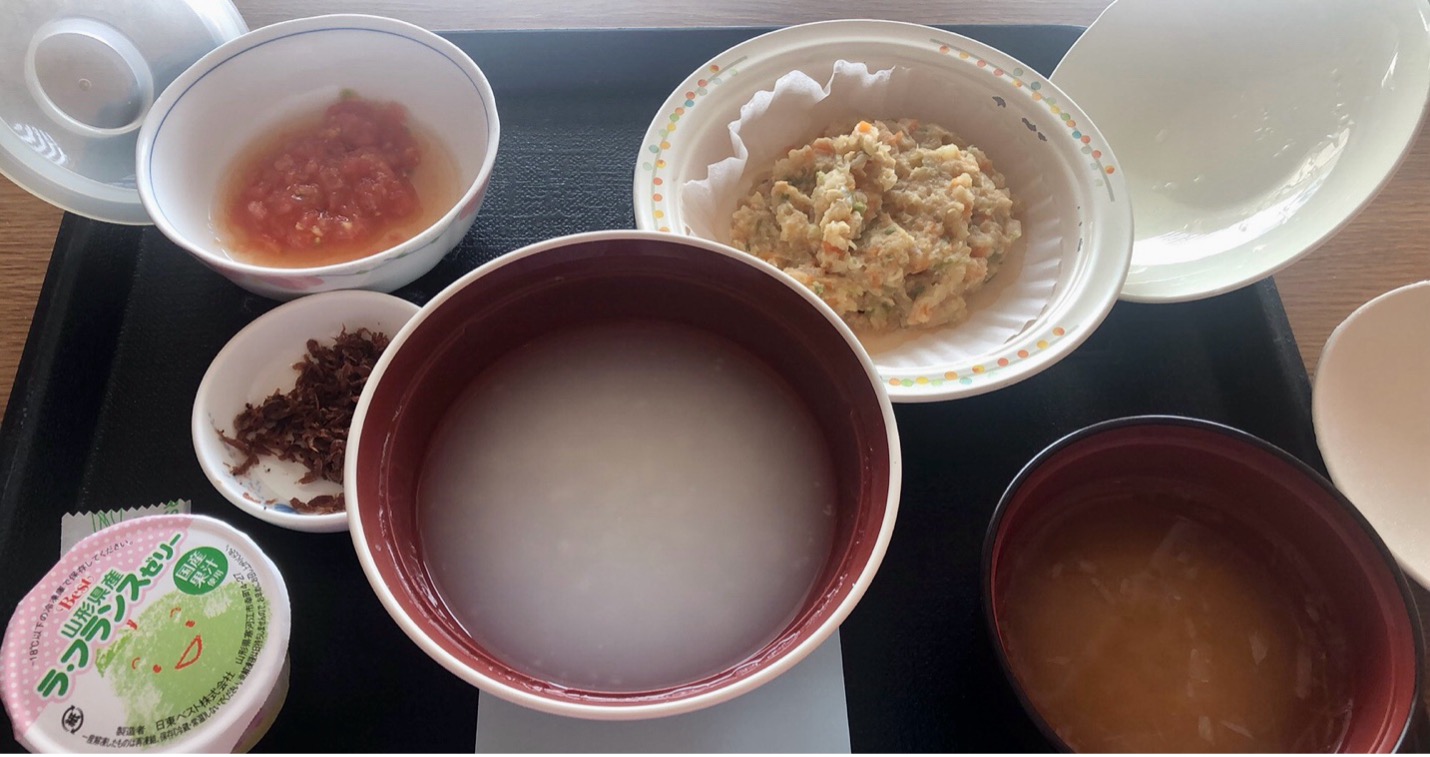

I can never forget the taste and smell of the first hospital meal after my colon polyp removal surgery. Nearly 24 hours after the ESD (Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection), I sat in my patient room and had the blandest meal that I can remember. It included a bowl of porridge with barely any rice, soft mashed vegetables, dried bonito flakes, and miso soup with no visible ingredients. On the tray there was my name tag, marked by “gastrointestinal post-op set” label and a barcode. After three days of hospitalization, I was finally allowed shredded cabbage with ham, soft white rice, and a small piece of bread from the convenience store downstairs—all embodying my recovery and readiness to go home.

Picture 1: First meal after the author’s ESD

The first time I lost the freedom to choose my food made me ponder hospital meals as an obligatory part of patient care at every Japanese hospital today. How did hospital meals come into being in modern Japan? Why did it become a compulsory part of patient care at hospitals? Through the prism of hospital meals, this essay offers a glimpse of changing patient care in Japanese history.

Mostly taking place at home, patient care in early modern Japan emphasized dietary modification for the purpose of smooth recovery. Diaries of Edo residents indicated that literate families referred to materia medica classics, popular food manuals, or woodblock prints for guidance on how to feed the sick at home. Adjusting patients’ diets in accordance with their changing symptoms every day, caretakers of the ill endeavored to offer foods that were beneficial rather than harmful to the patient’s health. For instance, for measles patients, daikon radish and Chinese yam were “good,” whereas river fish and tofu were “bad.” Constants existed too. Rice gruel (thin porridge), for example, was regarded as one of the most recommended staples for the sick, especially those “after a period of not eating” (Young, 68-86).

After the Meiji Restoration, development of modern nutrition science in Japan gradually transformed people’s perceptions of food and their perceptions of its relationship with sickness and health. In 1888, Juntendo Hospital physician Hirano Chiyokichi (平野千代吉) published the first manual of modern nutrition therapy New Theory on Food Therapy (Shokuji ryōhō shinron, 食餌療法新論). While acknowledging the effectiveness of some “old-fashioned” diets for the sick, the book reinterpreted and upgraded them with new nutrition knowledge. The following description of rice gruel exemplified such changes well. While suggesting feeding rice gruel to patients with weakened digestive system, Dr. Hirano advised adding protein-rich food to nurture patients better:

Rice gruel can be used to feed patients with acute disease, inflammatory, or febrile diseases. Boiled porridge should be fed to patients with weakened digestive system. It is especially beneficial to add milk, cheese, butter, and egg, and make it into “pudding…” (Hirano, 45)

Apart from basics of food nutrition, Hirano introduced special diets for medical conditions ranging from stomach ache and constipation to diabetes and skin problems (Hirano, 6-7). He also pointed out the importance of dietary diversity and respect for patients’ preferences. Eating would harm patients’ digestive function, such as if one single kind of food was offered too often, or foods were cooked without considering patients’ taste (Hirano, 59).

A few decades after the publication of Hirano’s manual, more systematic study of patients’ diets in Japan began at Keio University Medical School in the 1920s. In 1924, riding on the wave of widely spreading social attention to food and nutrition issues in post-WWI Japan, Keio University professor Ōmori Kenta (大森憲太) proposed the establishment of a new research institute dedicated to studies of patients’ daily intake. Receiving generous support from entrepreneurs running Japanese conglomerates like Mitsubishi and Mitsui groups, the Institute of Food Nourishment Studies (Shokuyō kenkyūsho, 食養研究所) was founded in 1926 (Ikai jihō, June 28, 1924, 1195; The Nippon Medical World, December 1926, 19).

As a center of research on patients’ diets, the Institute organized training courses and invited physicians of different expertise to share their clinical experiences. In 1931, the Institute published the culmination of years of hard work. The book titled Nutrition Therapy (Shokuyō ryōhō, 食養療法) shared disease-specific diets with detailed ingredients, nutritional composition and calorie count. They were all designed or used clinically by doctors working at hospitals. It introduced new methods to feed patients who could not or refused to eat, such as rectal alimentation, parenteral nutrition, and nutrition via subcutaneous injection (Ōmori, 292). Keio University Hospital nurse Nakamura Fujiko (中村ふじ子) also shared her wisdom gained from everyday patient care. She believed that offering food that “smelled nice, tasted great, and looked pretty” should not be considered a luxury, but a vital part of patient care. Whoever cooked for the sick ought to “empathize with them by respecting their dietary preferences and feelings.” (Nakamura, 332).

In 1933, Keio University Hospital established its new Nutrition Department to put works done by the Institute of Food Nourishment Studies into practice. For the first time in modern Japan, a hospital, instead of family members, cooked food and fed their inpatients. From the 1930s till the end of WWII, many hospitals in Tokyo established in-hospital kitchens and incorporated hospital meals in their inpatient care system. They often shared menus and recipes of disease-specific diets in medical journals (see picture 2). The medical journal dedicated to hospital management and treatment, Hospital (Hosupitaru, ホスピタル), even regularly published recommended hospital meal menu every other month (“Byōin kondate,” February 1940, 34).

Picture 2: A menu for patients with digestive diseases at Tokyo Imperial University Hospital. On the top it said: “No fish or miso. Two eggs and two bottles of milk every day. Must guarantee 40g of protein. Calorie intake varies in accordance with staple intake.”

Not every Japanese hospital embraced this hospital meal system right away. Right after the end of WWII, many patients still carried pots and pans to their hospital rooms. In the room or at the hallway, they would cook for themselves or have their families help them. Some would pack their meals made at home (Nakamura, 316-7). However, nutritional and sanitary concerns often accompanied hospital self-cooking which was eventually banned. In 1950, hospital meals became a part of compulsory inpatient care at every hospital in Japan.

Hospital meals symbolize a transformative change in patient care, particularly for those that need hospitalization. No longer a job for the families of the sick, feeding the patient became hospitals’ responsibility. While this system has been gradually adopted by Japanese hospitals since the 1930s, the content of such meals became more regulatory than individualized. Regardless of patients’ personal taste, hospitals offered the same food to patients with the same disease. Labeled by their sickness, patients became voiceless (if not impersonalized) to nutritionists who “governed” their daily dietary life.

Pictures:

- Photo taken by author during hospitalization.

- Menu for patients with digestive diseases, at Tokyo Imperial University Hospital. From Japan Medical Women’s Journal, 97 (July 1940), p. 23.

Works cited:

“Shokuyō kenkyūsho rakusei hirokai,” The Nippon Medical World, December 1926, p. 19.

“Keidai shokuyō kenkyūsho kensetsu shinchoku,” Ikai jihō, June 28, 1924, p. 1195.

Chiyokichi Hirano, Shokuji ryōhō shinron, Tokyo: Hirano Chiyokichi, 1888.

William Evan Young, Family Matters: Managing Illness in Late Tokugawa Japan, 1750-1868. Dissertation, Princeton University, 2015.

“Byōin kondate,” Hosupitaru, no. 191 (February 1940), p. 34.

Teiji Nakamura, “History of Japanese nutrition therapy and response to an aging society,” Journal of Japanese Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, vol. 34, no. 5 (2019), pp. 316-9.

Igakubu no setsuritsu to keio igaku no kakuritsu, https://www.med.keio.ac.jp/about/history/1917.html. Accessed March 2, 2024.