The historian Roy Porter observes that “We turn doctors into heroes, yet feel equivocal about them […] Even in Greek times opinions about medicine were mixed; the word pharmakos meant both remedy and poison – ‘kill’ and ‘cure’ were apparently indistinguishable” (4). This paradoxical mixture of killing and curing is perhaps nowhere more visible than in the practice of medicine in times of war, where the apparently life-saving practice of medicine comes into direct contact with the life-taking practice of war. As the ethicist Michael Gross notes, “War takes innocent lives and only some goal of greater value can ever justify this. Along the way, compelling norms that ordinarily protect life and dignity may fall” (249).

Medicine is not immune to the threat of the breakdown of norms in wartime, a conundrum starkly illustrated in literary depictions of the Russian Revolution and Civil War. For instance, in Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago, the protagonist Yuri Zhivago is captured by Bolshevik partisans and compelled to act as their doctor. The narrator tells us that, “According to the Red Cross International Convention, the army medical personnel must not take part in the military operations of the belligerents. But on one occasion the doctor was forced to break this rule. He was in the field when an engagement began and he had to share the fate of the combatants and shoot in self-defense” (332). Despite doing his best not to hit anyone, Zhivago wounds a young White soldier. Zhivago and a trusted confidante manage to rescue and take care of the man, and “When he was well they released him, although he did not conceal from them that he meant to go back […] and continue fighting the Reds” (336). In this case, Zhivago violates a tenet of medical ethics (“the army medical personnel must not take part in the military operations of the belligerents”) by wounding a man in battle. However, he redeems himself by upholding another ethical principle – taking care of those who need medical help regardless of political affiliation. The doctor almost kills, but it is his role as a curer that eventually has the upper hand.

Not all literary depictions of the war allowed for this kind of redemption, however. The poet Marina Tsvetaeva recalls hearing a story of a woman whose doctor fiancé was killed for performing a similar action to Zhivago. In the woman’s account, “My Kolya left the house […] And a man fell right at his feet. All bloody. And Kolya’s a doctor, he couldn’t leave someone who’s wounded. He looked around: no one in sight. So he took him, dragged him into his own house and looked after him for three days. He turned out to be a White officer. And on the fourth day they [the Bolsheviks] came, took them both, and shot them together…” (60). Unlike Zhivago, Kolya is not responsible for the man’s injury and thereby remains morally unscathed, but he pays with his own life for upholding the ethical principle of not “leav[ing] someone who’s wounded,” as a doctor.

Perhaps an even more ambiguous depiction of the doctor in wartime is found in Mikhail Bulgakov’s short story “The Murderer.” At a social gathering, the narrator, also a doctor, expostulates, “Murder is not part of our profession. How can it be?” (163). This prompts the surgeon Yashvin to tell his story. Despite his tsarist sympathies, Yashvin is conscripted by Symon Petlyura’s Ukrainian Nationalist forces to serve as their doctor. Yashvin, however, shoots a colonel to protest the beating of a woman. After hearing the story, the narrator asks, “Did he die? Did you kill him or only wound him?”, to which Yashvun responds enigmatically, “Oh, don’t worry – I killed him all right. Trust my experience as a surgeon” (176). Yashvin’s response is disconcerting, as he implies that he used his medical knowledge to ensure that the man was in fact dead. In this story, unlike in the previous two the doctor does not participate in any kind of curing (although he is attempting to serve some kind of just cause by defending the woman), and is instead wholly identified with killing – the title of the story, after all, is “The Murderer.”

Perhaps we would like to think of medical ethics as being universal enough to transcend context. However, as these stories illustrate, when larger norms that preserve the sanctity of human life are weakened, the norms governing the life-preserving practice of medicine become vulnerable too. War reveals both sides of pharmakos – the killing and the curing together.

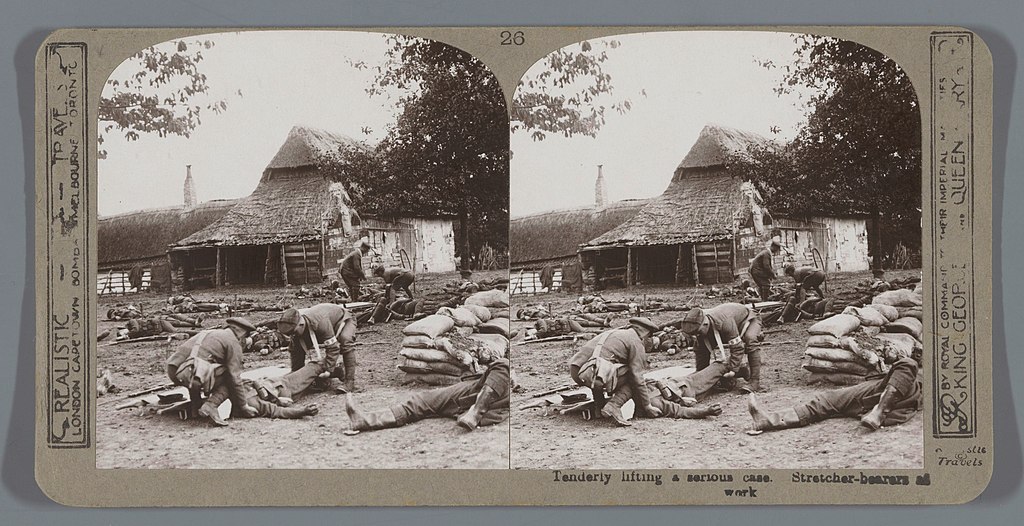

Image Credit: Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/34/Soldaten_leggen_een_gewonde_op_een_brancard_Tenderly_lifting_a_serious_case._Stretcher-bearers_at_work_%28titel_op_object%29%2C_RP-F-F06280.jpg

Works Cited

Bulgakov, Mikhail. “The Murderer.” A Country Doctor’s Notebook. Translated by Michael Glenny, Melville House Publishing, 2013, pp.161-76.

Gross, Michael. “Military Medical Ethics in War and Peace.” Routledge Handbook of Military Ethics, edited by George Lucas. Routledge, 2015, pp.248-64.

Pasternak, Boris. Doctor Zhivago. Translated by Max Hayward and Manya Harari, Pantheon Books, 1958.

Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. W.W. Norton, 1998.

Marina Tsvetaeva. Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries 1917-1922. Edited and translated by Jamey Gambrell, Yale University Press, 2002.