Jessica M. E. Kirwan

In June of 1888, German Emperor and King of Prussia, Frederick III, died of a laryngeal tumor at the age of 56, only 99 days into his reign. His death is considered one of the greatest malpractice cases in history, and, while most discussions center around the illness itself, here I would like to briefly review what Frederick’s diagnosis and treatment can tell us about the practice of medicine and its professionalization in Europe in the late nineteenth century.

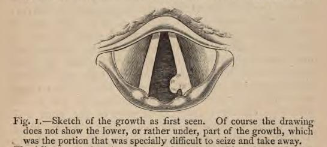

The story begins in the spring of 1887 when Frederick’s team of German physicians, led by Karl Gerhardt, noticed a nodule on his vocal cord. Gerhardt attempted to remove and cauterize the nodule, but Frederick’s symptoms worsened and they soon diagnosed him with laryngeal cancer. Nevertheless, they sought another opinion, this time from the British “father of laryngology,” Dr. Morell Mackenzie. Mackenzie attempted a diagnosis by using a somewhat new technique, the laryngeal biopsy. After removing tissue from the mass, it was given to Prussian pathologist Rudolf Virchow to analyze. Virchow saw no cancer cells under the microscope, and Mackenzie, by now having taken the lead in caring for the Emperor, treated the mass as benign. Eventually, however, the tumor grew and the Emperor’s health deteriorated. Cancer became all too evident and Frederick desperately yielded to a risky laryngectomy in November. The laryngectomy did little to ease Frederick’s pain or cure his cancer. He died four months later. As a result of Frederick’s case, laryngeal biopsy was abandoned as a diagnostic technique for decades, during which time biopsies were used to diagnose other cancers.1

In addition to setting a diagnostic standard for laryngeal cancer, Mackenzie and Virchow’s misdiagnosis led to the end of Mackenzie’s career despite his illustrious successes in the preceding three decades. He would spend the few remaining years of his life defending his treatment of the Emperor. Gerhardt and his German colleagues claimed Mackenzie lacked the expertise to treat the Emperor2 while the German people suspected a conspiracy.3 They pointed to British medical publications legitimizing Mackenzie’s diagnosis and treatment as propaganda.2 Before the end of the year, Mackenzie, haunted by the loss of his reputation among colleagues and patients, would publish a book of over 250 pages about the Emperor’s case.4 But it did not save his career. Virchow, by contrast, was given the benefit of the doubt and continued his celebrated career. After all, he had proved his loyalty to the German people during the German revolution and later by holding political office.

Since his death, Frederick’s illness has been discussed as one of the most influential medical cases in history. In recent decades, historians and physicians have re-imagined the ways in which the misdiagnosis changed the course of European history when a peace-loving ruler was replaced by a war-mongering one. However, while the Emperor’s cancer may have been treatable at an earlier stage, such re-imaginings are grounded more in fiction than fact. Any cancer surgery at that time, specifically the laryngectomy, or thyrotomy, would have been a high-risk procedure more likely to result in severe morbidity (like losing one’s voice) and death than cure and comfort, a fact Frederick’s doctors understood.1 Nevertheless, today the popularly entertained perspective of the Emperor’s death has been that, were he properly diagnosed and treated, events in Europe since the late nineteenth century up to both World Wars would have transpired differently, and millions of lives could have been saved.

While modern retellings tend to focus on the case’s influence in leading to both World Wars, returning to the reports of Frederick’s illness written before and shortly after his death elucidate the nationalist and cultural undertones to the dispute, undertones that resonated throughout the medical profession at the time. All of Europe had its eyes on the Emperor and projected onto his body their own cultural, political, and professional ambitions. In October of 1888, four months after Frederick’s death, the British Medical Journal published their attempt at a balanced view of the Emperor’s case, drawing from previous British and German publications. In the article, the politicization of the case is characterized as “disfiguring” and the author refers to any discourse beyond the medical analysis as an “excrescence,” or growth.2 For the author of this case report, therefore, a balanced analysis was meant to work as a cancer surgery—an attempt at an immediate intervention in the narrative of what occurred. The article nevertheless pitted the German and British physicians against one another, much like the case reports preceding it, by re-telling the events as they happened according to one side and then the other.

At play in the narrative of Frederick’s treatment was the German doctors’ skepticism about microscopic diagnosis and Mackenzie’s over-reliance on it. The German doctors’ concern further questioned Mackenzie’s credentials and expertise, suggesting he did not perform the examination properly and was in fact hasty. That Mackenzie relied on Virchow was viewed by Gerhardt as a “shifting” of responsibility.2 Further, Frederick’s German doctors felt shut out from treatment of their Emperor since Mackenzie continued reporting on his condition in British medical journals despite their disagreement with his conclusions. The German doctors believed Mackenzie was turning public opinion away from their initially accurate diagnosis and toward his own faulty one. The October 1888 BMJ summary of reports further shows that it was not only the Emperor’s health at stake, and potentially the future of the German and British Empires, but also the professionalization of medicine itself. Characterized as a “great tension in the relations of the English medical attendants with their German colleagues,” the discord between Dr. Gerhardt’s team and Dr. Mackenzie’s reflected the pressure in the medical field for professional unity.2

In his essay, “Between scrutiny and treatment: physical diagnosis and the restructuring of 19th century medical practice,” Jens Lachmund discusses the pressure among European doctors to homogenize medical practices, a pressure reflected in the diagnosis and treatment of Frederick.5 While Frederick’s German doctors believed his symptoms and their thorough physical examination revealed cancer, Mackenzie relied on more advanced pathologic diagnosis.

As Lachmund argues, changes in diagnosis required “re-negotiation of the deeply entrenched modes of interaction” both between doctors and patients as well as doctors and doctors.5 Mackenzie struggled against the expectations of modern medicine, and it failed him. Frederick’s German physicians capitalized on that failure to argue for their more traditional method of diagnosis. In the October 1888 BMJ article, Frederick was characterized as the “heroic” patient-soldier who, under the power of his enemy, “received…a sentence, not only of death, but of prolonged suffering.”2 Yet whether the enemy was the cancer or his contentious German and British physicians arguing over the superior method of diagnosis and treatment was left unclear. Frederick’s death was a medical failure that needed to be regulated, understood, explained, and neutralized so as not to discredit the value of medicine. Disease was more than a diagnosis or described pathology; it was a succession of theories leading to observations, accidents, wrong turns, and national conspiracies—an attack on perception and truth——and a means to determine the future of one’s nation. To reach a consensus among the physicians, and salvage the validity of medical diagnosis itself, Frederick’s original doctors saw no choice but to pursue the narrative of Mackenzie’s malpractice, even if it carried political implications. Sadly, pinning Frederick’s death on Mackenzie ultimately led to his deteriorated health and death.

Although the exact cancer Frederick suffered and died from has never been determined, what is clear is that, because the Emperor died, his German doctors were able to discredit Mackenzie’s approach, ultimately discrediting pathologic diagnosis for laryngeal cancer, despite their national ties to the father of pathology, Rudolf Virchow. Frederick’s illness was unique in that it laid open the political and cultural discord between two nations. Furthermore, it was unique in that an individual’s illness single-handedly determined the standard-of-care diagnostic technique for several generations to come owing to the potential that a diagnosis can change the course of all of European history and spark two wars. The Emperor’s case appears to be singular in its influence; and while the continuing narrative that a misdiagnosis caused both World Wars is misguided, the narrative surrounding his illness and death nevertheless signals a pivotal moment in the effort to homogenize medicine as a legitimate profession, despite the ambiguity of the therapeutic outcome.

Featured Image: Morell Mackenzie, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

- Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Lascaratos J. Highlights in the evolution of diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal cancer. Laryngoscope. Mar 2003;113(3):557-562.

- The Case Of The Late Emperor Frederick British Medical Journal. October 13, 1888;2(1450):836-841.

- Androutsos G. Illness and death of the Kaizer Frederick III (1832-1888). The tremendous impact on politics. J BUON. Oct-Dec 2002;7(4):389-395.

- Mackenzie M. Case of Emperor Frederick III: Full Official Reports. New York: Edgar S. Werner; December 1888: https://archive.org/details/caseofemperorfre00mack. Accessed September 19, 2017.

- Lachmund J. Between scrutiny and treatment: physical diagnosis and the restructuring of 19th century medical practice. Sociology of Health & Illness. November 1998;20(6):779-801.