Gabi Schaffzin // A few hours after knee surgery, a nurse or doctor might come into your room and ask how you’re feeling. They might show you a scale of 6 faces like this:

Maybe a notched line like this:

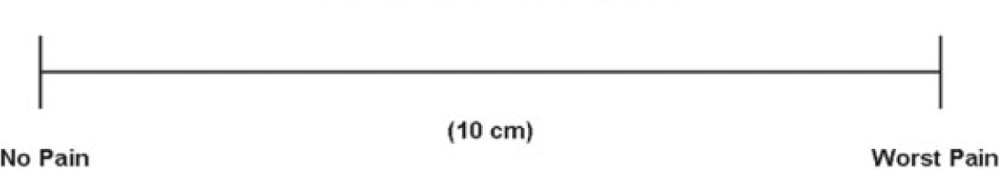

Or, they might show you this line. It will probably have two phrases on it:

The practitioner speaking with you will ask you to point to the line. You’re a bit groggy and your mouth is dry—or maybe it’s not your knee, but your jaw that’s been operated on. Or maybe you are a non-verbal communicator even when you’re not under the influence of whatever they hopped you up on to help with the pain they’re currently measuring.

So you point somewhere on the line. Maybe, let’s say, just to the right of middle. That point is marked and measured: 5.5cm. Not the worst pain, but not great.

A few hours later, they come back. Maybe it’s someone new. They ask you to point again. This time it’s 7.1cm. The drugs are wearing off. Your answer is noted.

The tool that these practitioners have been using is called the Visual Analog Scale for Pain—or VAS. Medical practitioners like the VAS for a few reasons. The first is that your answer is immediately converted to a numeric value without your needing to think of numbers. Secondly, unlike the graduated or faces scale, it does not lead the witness: you aren’t drawn to a full integer. Along these same lines, the answer you give is not pre-delineated. Which means that whoever is using that data can do so in whichever way they’d like. I already decided that your answers were to the nearest tenth of an integer. Perhaps we’re working in a study that requires an evaluation at the nearest hundredth. We can adjust your values by just re-measuring your answer.

These justifications for the use of the VAS are all predicated, of course, on the assumption that your caretaker is interested in quantifying your pain. Why on earth would they want to do that?

Dr. Henry Beecher was head of anesthesiology at Massachusetts General Hospital from 1936 to 1969. During those years, he published extensively about the ethics of using human subjects in medical studies as well as on the placebo affect. He also spent time in North Africa and Italy during World War II. It was here that he developed his ideas about the subjectivity of pain, which he eventually published Measurement of Subjective Responses: Quantitative Effects of Drugs, in 1959.

In the work, he argued against a then prevalent approach to the measurement of pain: the dolorimeter. This was a device that had been invented and re-invented many times in the centuries prior, but in the 1940s, it was a 1000 watt bulb projecting a strong beam of light, which was focused through a fixed aperture onto a small area of a person’s forehead that had been blackened with China ink (to control for differences in skin pigmentation). A patient’s pain threshold was measured by time: how long could they leave the beam of light burning their foreheads.

The goal for inventors of the dolorimeter was to standardize the measurement of pain—to be able to garner reliable and reproducible results from a small sample size. At the time, most pain-related trials were, as they are today, related to understanding the effects of various drugs, but back then they were primarily being run by the Committee on Drug Addiction and Narcotics, a government body. So running reliable studies on the cheap was critical.

But then Beecher came along and suggested considering each patient’s experiences as different—from their individual background to literally what is happening to them at the time that they feel pain. This was an idea he developed after watching soldiers forgo morphine as the adrenaline of battle was still pumping through them, but seeing a very different story away when things settled down.

For a plethora of reasons, Beecher’s subjective approach—which included asking each individual how they felt at any given moment—pushed the “objective” approach of the dolorimeter out. After making major investments and resulting strides in synthetic opiate research, World War II-era pharmaceutical companies (they were primarily German corporations) were taking over the responsibility of drug trials. With the money they were throwing into the studies, they could afford a much larger sample of subjects—this was a shift from as few as three subjects in a dolorimeter study and a few hundred dollars to purchase the device and train its operator to Beecher’s subjective studies, which sometimes required hundreds of patients over the course of a number of weeks.

As clinical pain trials grew in size, then, the amount of data being collected would have to be done using tools that were quick, flexible, and extremely effective. Enter the VAS, with its extensive use in psychological studies during the first half of the 20th century. It was used to assess all kinds of subjective states, like sadness, happiness, loneliness and even vulnerability.

The idea that pain might be a subjective experience, then, is relatively young—even as corporations and governments alike seek to build tools predicated on the contrary. The VAS, however, goes back quite a bit further than Beecher’s time. In my next post, I’d like to explore where psychologists and psychiatrists picked up the VAS—a history that not only recontextualizes the way we think about contemporary methods of quantification of pain in the body today, but also makes an argument about the ways that the history of design is taught in the academy.