Josh Franklin //

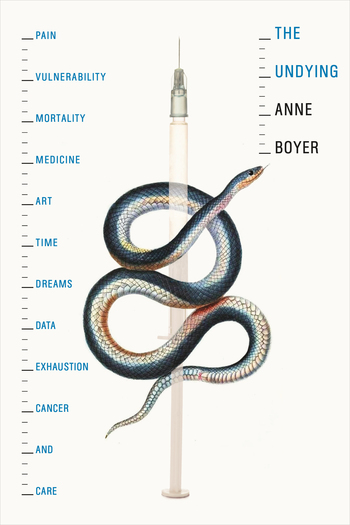

Review of Anne Boyer. The Undying. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019.

The Undying is a powerful memoir by poet Anne Boyer, describing her diagnosis of breast cancer and her subsequent treatment. Boyer struggles against the narrative confines of the illness experience as conventional and medicalized, writing, “I do not want to tell the story of cancer in the way that I have been taught to tell it.” Through this, what emerges is a text that is both deeply moving and insightfully critical.

Among the many reasons it is challenging to write a book about breast cancer, perhaps the most daunting is the fact that this book adds to a deep body of work on the subject, from the academic to the literary, the personal to the political, the tragic to the triumphant. As Boyer writes, “The silence around breast cancer that [Audre] Lorde once wrote into is now the din of breast cancer’s extraordinary production of language. In our time, the challenge is not to speak into the silence, but to learn to form a resistance to the often obliterating noise.” While Boyer sets herself against much of the contemporary discourse of breast cancer, she finds a resonance with the writings of Audre Lorde, as well as anthropologist S. Lochlann Jain’s Malignant, Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor, and others. This body of work presents a deep challenge as well as a tantalizing possibility for Boyer: “If few diseases are as calamitous to women in effects as breast cancer, there are even fewer as voluminous in their agonies. These agonies are not only about the disease itself, but about what is written about it, or not written about it, or whether or not to write about it, or how.”

So from these very beginning references, The Undying is clear to tell us that it is not an atomized tale of suffering or an individual narrative of struggle and victory, but rather a collective account. Boyer rejects the affective purchase of a medical story in favor of the possibility of writing to evoke a collective and reveal the ways that our lives are diminished by human forces beyond our control. Boyer foregrounds this literary heritage immediately, aiming to break free from the personalizing conventions of the memoir in order to write for a kind of collectivity. She names this collective not in relation to breast cancer, patienthood, or survivorship, but by the term “woman.” She tells us, “Cancer is in our time and place one of the most effective diseases at eradicating the precise and individual nature of anyone who has it, and feminized cancers—in that to be seen as a woman is also to be, in a way, semi-eradicated, this eradication deepened by class, race, and disability—even more so.”

The violence of medicine, in particular, is a central theme of Boyer’s sharpest writing in The Undying. “Oncology,” she tells us, “is a genius at the production of desolate feelings, which is why I will never believe that things were always as bad as they felt, even if they might have been worse. During diagnosis, the sick are kept in cold rooms while the technicians stand in other rooms, behind glass, talking to us through headphones. The surgeons label our body parts with purple pens. Some loved ones abandon us. Strangers fetishize our suffering.” She also writes particularly poignantly about the abandonment and indifference of her mastectomy, performed at an outpatient surgical center. “After my mastectomy, the eviction from the recovery ward came aggressively and early. The nurse woke me up from anesthesia and attempted to incorrectly fill out all the questions on the exit questionnaire for me while I failed in an attempt to argue with her that I was not okay.”

While it is a cliché, this work could certainly be considered “required reading” on the subject, especially for health workers who urgently need this reminder about the violence of medical practices we now call care. Yet, as Boyer reminds us near the end of the book, “Nothing I’ve written here is for the well and intact, and had it been, I never would have written it.”

The Undying reveals the structural and chronic nature of these forms of suffering it chronicles. It also asks us: where to go now with this text that has made clear that to tell a conventional narrative would be to capitulate to precisely the violent forces that preclude our attempts to care for each other and ourselves? It is an indeterminacy that she seems to wrestle with throughout the text. “In pain,” she writes, “there is always something to explore, but never anything to conquer. There’s no empire in a nerve.”

Boyer’s ability to stay with these painful ambivalences and questions is strikingly showcased as the text nears its conclusion and turns to the theme of exhaustion. She describes exhaustion in language that is increasingly elliptical, and which never quite reaches the clarity of a resolution. Rather than reorganizing this story to either emphasize the obstacles or obscure them, the form of the book illustrates precisely this urgent message about the power of what is misrecognized as care in late capitalism to drain us of our energies. One could imagine a text that concludes by breaking with the experience-near language that preceded it in order to make a tidy set of critical observations. Boyer takes a different path, leaving the reader with a sense of unfinishedness that is deeply revelatory.