— Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture/I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident/

the art of losing’s not too hard to master/though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.Elizabeth Bishop, “The Art of Losing”

These lines from Bishop’s poem immediately encapsulate for this essay two points. That losing (specifically a loved one, you) is an art of mourning and coping that is mastered eventually. And that the urgent imperative – Write it! – represents the all too familiar notion of the written word’s cathartic power in the aforementioned coming-to-terms. And if one only reads the “you” as “I,” or the poem as a note to oneself, it slowly morphs into a lament for the loss/death of the self, and all the material memories it associates with.

Cancer writing, however, as seen in auto/biographical texts written by patients, caregivers and doctors, foregrounds that there is no complete mastery over the disease. These narratives embody and exercise, drawing from Leigh Gilmore’s study of chronic pain memoirs, an agency without mastery, in order to avoid universalizing triumphalism. They risk, in Gilmore’s words,

sacrificing the consolations of humanistic narratives that hold out hope for control and transcendence in the face of what is truly feared: the dissolution of self, the reminder of decay and death, a dependence on others through the loss of work, the financial stress of hospitalization and rehabilitation, and reminder of body as matter.” (91)

It follows that not all illness narratives would contain such an agency, but chronic illnesses like cancer demand a recognition of the fear of uncertainty and failure. Mastery, then, invoking Bishop again, would mean an acknowledgement and non-denial of the impending death, an invocation of memento mori.

This essay will focus on a genre that teeters on the edges of life writing and death writing, and is intended as the narrative reconstruction of one’s life – the self-obituary. The OED defines the obituary as a death notice, and the earliest obituaries showed in graphic detail the circumstances of death before moving on to a posthumous study of the subject’s life. The self-obituary – an obituary written by the subject before death – is prospectively posthumous, that is, it assumes a posthumous self that then seeks to describe the life that was. The agency of announcing their deaths lies with the subjects in the self-obituary. A precursor to this can be found in obit writing at the end of the twentieth century, when the NYT journalist Alden Whitman would conduct interviews of subjects before writing their obituaries, bringing to the obit writer the name “the recording angel” (Fowler 7). The phrase is important because it brings the concepts of witnessing and speaking from beyond – an angel being an intermediary, or even the spirit of the dead come back to deliver a message (OED) – to the fore. Deathwork, where communication occurs between the dead and the living is of different kinds. Tony Walter qualifies the obituary as mediator deathwork, where the writer of the obituary, acting as mediator, is in the business of “interpreting the dead to the living” (385). The autothanatography, death writing where the dead speak of their own death, appears inconceivable but is still possible, as literature has shown us with numerous examples – like the ominous “I am dead”, pronounced in Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Facts in the case of M. Valdemar.” Yet here I speak not of fiction but of writing that is autobiographical and written by the terminally sick.

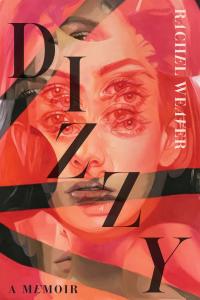

The self-obituary incorporates an affective retelling of the writer’s life and is inclusive of its many failings and hopes, as opposed to an obituary which is traditionally a list of achievements (though there exist the sub-genres of the critical and ironic obits as well, as Fowler outlines in The Obituary as Critical Memory). But this is also what the memoir can effectually do, present an affective account of the dying. What is the distinguishing grammar of the self-obituary then? Among the slew of obits and self-obits circulating in the media, one stood out to me for its formal features, offering some reprieve as to how a self-obituary can, indeed, possess a distinguishing narrative feature.

The essay “You May Want to Marry My Husband” by Amy Rosenthal appeared in the Modern Love column of the NYT and went viral very soon after. Rosenthal writes under a pressing deadline in the form of her failing health due to cancer. The essay takes on a form of public addressal, but stands out because the writer addresses not merely her own life, but decides to make some plans for her husband after she is dead, as the title of her essay suggests. The essay ends with an empty space, where Amy Rosenthal invites her husband to write a fresh life for himself with someone else. A year later, the NYT published a response from her husband in the same column, where he expressed his gratitude for the overwhelming response his wife’s essay received. He ended his own response with yet another empty column, which he explained thus:

My wife gave me a gift at the end of her column when she left me that empty space, one I would like to offer you. A blank space to fill. The freedom and permission to write your own story.

The empty space is a rupture from a self-referential world. If the self-obituary is a boundary crossing practice, one where writing of the dead speaks to the living, the direct beckoning of the living (a different diegetic universe, surely?) to speak back/ahead in the self-obituary is a metaleptic rupture. Metalepsis is a narrative tool that indicates the narrative shift from one diegetic level to another, and the way Genette describes it, as a means of “taking hold of [telling] by changing levels” (45) almost has an agentic ring to it, that of narrative control. The auto-thanatology, of which the self-obituary is surely an example, works as “a study of the impact of death’s completed approach on one writing a self-portrait” (Callus 432). Metalepsis stresses also on the temporal differences between the time in narration and the time of narration. The self-obituary is thus an agentic device for the dying to move forward through time and assume a dead self that can describe itself, and communicate to the bereaved. The space in Rosenthal’s essay is a pause, from which another narrative emerges, by another person.

In The Work of Mourning, Derrida seeks a singular detail, a punctum, from which to instantaneously access Roland Barthes after his death, something from Barthes that would call out to Derrida, address him, as a punctum to the witness of a photograph. Derrida interprets Barthes’s opposition of the studium/punctum in the photograph as representative of all conceptual oppositions, but also an opposition that facilitates a composition, one that captures a relationship of haunting:

They compose together, the one with the other, and we will later recognize in this a metonymic operation; the “subtle beyond” of the punctum, the encoded beyond, composes with the “always coded” of the studium. (41)

The empty space Rosenthal inserts at the end of the obituary is a graphic invocation of death, both a visual representation of absence, and a call to the mourner to interiorize the posthumous-self-to-be in a lamentation. The digital self-obituary can then inherently simulate this defining feature of opposition and composition of the stadium/punctum, acquiring a graphic property analogous to the photograph.

What does this do, the metaleptic rupture that pauses and beckons to the living from the grave? The self-obituary is a means for the dying to extend care to the living, a gift of reciprocity and a means to partake in mourning. The self-obituary is a means of posthumous care – both for the bereaved and the dying self. The term “literary care,” proposed in Katherine de Moore’s study of witnessing in AIDS memoirs, lends itself well to the narrative genre of the self-obituary, which functions as “the sort of witnessing that is constructed, implicitly or explicitly as an extension of practices of care and a continuation of the caring process” (208). What is implied here of course is that mourning (of the self as well ) is a form of witnessing, where both processes rely on remembering and recalling.

Among the several means now identified by the ill and dying to shape the experience of remembering for the bereaved is “death-cleaning,” a process that Margareta Magnusson writes about in her book The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning and Nancy Miller acknowledges in an essay “Death Cleaning and Me,” as being not just a means of leaving less clutter for her survivors but serving as an “art of memory” or an “art of life” (May 2019). Susan Gubar, diagnosed with late-stage ovarian cancer and writing the blog “Living with Cancer” for the NYT, writes of the self-obit,

It may be crucial in getting the facts straight and in conveying the import of an existence as well as the values informing it. Far from seeming narcissistic, undertaking a self-obituary can be a form of summation and of caregiving for those who may be in need of direction after we are gone. (July 19, 2018)

Gubar recalls annotating the margins of a canned obituary with her own notes on what it felt like to receive her diagnosis: she wrote what she calls an Obitchuary, a therapeutic process, but an obituary that she must keep editing – revising, splicing, rearranging – as each year passes by when she is still, indeed, alive.

Ivan Callus ends his piece on the autothanatography poring over whether even the extreme of examples can change the fact that “the writing of the dead” is, after all, “the script of the living”. Perhaps not, though this essay offers another consideration, that the genre of the self-obituary, an exemplar of the writing of the dead, is a script to the living, as much as it is of.

Works Cited

De Moor, Katherine, “The Doctor’s Role of Witness and Companion” Medical and Literary Ethics of care in AIDS Physicians’ Memoirs,” Literature and Medicine, vol. 22, no. 2, 2003, pp 208–229.

Callus, Ivan, “(Auto)Thanatography or (Auto)Thanatology?: Mark C. Taylor, Simon Critchley and the Writing of the Dead,” Forum for Modern Language Studies, vol. 41, no. 4, October 2005, pp. 427–438.

Derrida, Jacques, “Roland Barthes,” The Work of Mourning, University of Chicago Press, 2001, pp. 31-67.

Fowler, Bridget. The Obituary as Collective Memory. Routledge, 2007.

Gilmore, Leigh. “Agency Without Mastery: Chronic Pain and Posthuman Life Writing.” Biography, vol. 35, no.1, 2012, pp. 83-98.

Rosenthal, Amy Krouse. “You May Want To Marry My Husband.” Modern Love, The New York Times, 2017.

Walter, Tony, “Mediator Deathwork.” Death Studies, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 383-412.

Image source: Obituary of eminent persons and private friends. Wellcome Collection.