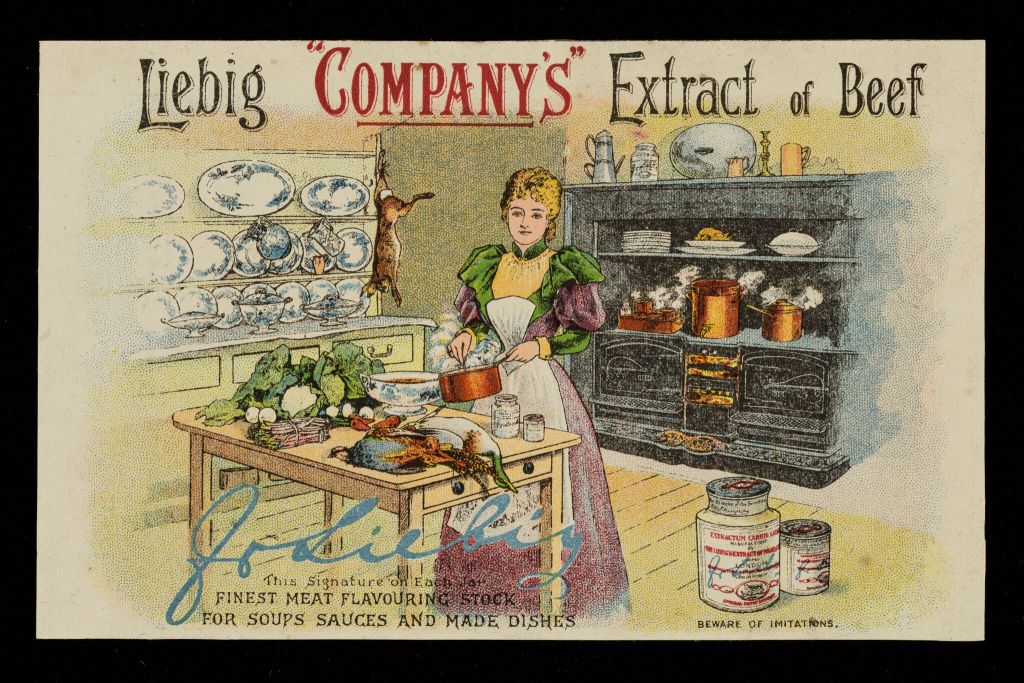

Baron Justus von Liebig carved out his name among one of the most influential yet now-forgotten figures in the history of chemistry. A major contributor to the development of fertilizer and its techniques for use, Liebig made an equally indelible mark on the landscape of mass-marketed foodstuffs, with his development of dried milk, his investigations of the best mode of coffee-brewing, and the elaboration of his Extractum carnis, or Beef-Tea, put on the market in 1865. Liebig’s contributions to agricultural chemistry, and the chemistry of food, both engendered the massive deployment of industry to capitalize on his expertise. Crucially, the widespread popularity of Liebig’s Beef-Tea can, in some ways, be examined as one of the first industrially-produced foods packaged with a corresponding wellness-based marketing message.

Liebig’s privileged position in the world of science and medicine in the first half of the nineteenth century indubitably informed the public’s understanding of the Extractum carnis in its early years. Having established the principles of nitrogenous and non-nitrogenous foods in his 1842 book Animal Chemistry, or, Organic Chemistry in its Applications to Physiology and Pathology, Liebig largely shaped the Western principles of nutrition that defined the next 20 years. Claiming that only nitrogenous foods (e.g., meat, eggs, legumes) could sustain animal life, enable the body to generate heat, and execute work, Liebig underscored how critical its consumption was to the health of the individual body, as much as that of the collective.[1] Liebig’s valuation of meaty substances led to a number of economic crises, and for the public to assert it was a duty to provide an accessible means of acquiring the necessary nutritive matter.[2]

Though Beef-Tea, or the Extractum carnis was initially conceptualized as a kind of ‘health food’, its rarity reserved its use to the sickly, who themselves had difficulty attaining it, according to physician William Beneke’s 1851 contribution to The Lancet. Having himself utilized the substance in the treatment of ‘scrofula and phthisis, […] ulcerations, dygpepsia, tubercular deposits in the intestinal glands, &c.’[3] The restorative properties promised by Liebig were evocative of the discourse around the enlightenment era’s Parisian ‘Restaurant’—a substance which would enable the body to sustain itself without the burden of digestion.[4]

Approached in 1862 by George Christian Giebert, Liebig was urged to invest in the purchase of a beef-salting plant in Villa Independencia, soon renamed Fray-Bentos.[5] The 28,000 acre plant on the Uruguay river soon started production, with Liebig’s endorsement, and capital raised by Antwerp entrepreneurs Cornelle David, Otto and George Gunter, Josef Bennett and from South American Ranchers.[6] The locale was perceived to be the solution to increasing problems of meat supply to Europe—the commonplace slaughtering of cattle for their hides with very little use of their flesh for commercial trade created an abundant market of affordable meat in the 1860s, which could only be exploited with the local manufacture of a product that did not require reliable refrigeration.[7]

Using 34 lbs of beef to produce one pound of extract, Liebig’s Extract of Meat was first believed to be so potent it could replace the consumption of meat altogether, with one pint of Beef-Tea equating to roughly eight ounces of its solid counterpart.[8] The product was considered a major breakthrough, and its newfound availability on the market was perceived as a long needed response to consistent crises within the European food system.[9] As historian Mark Finlay states:

For physicians, it apparently offered a convenient alternative to home-made beef teas—products they had already endorsed and prescribed for convalescing patients. Meat extract fitted military planners’ criteria as well, for it did not spoil, and it was portable, lightweight, consistent in quality, and easily reconstituted into a soup that could feed large armies. For those concerned about adulterated or overpriced beef, it seemed to defeat decisively unscrupulous meat salesmen. Meat extract also appealed to domestic science writers who promised to bring rationality and convenience to the kitchen. For social reformers and statesmen, it seemed to offer a way to alleviate political crises by keeping the lower classes fed and peaceful through meat-based soups.[10]

By determining five separate appeals of the extract, Finlay successfully highlights the marketability of the Liebig Extract of Meat Company (LEMCO) product, which was nearly unparalleled.

After launching a test product in 1862, LEMCO was founded in 1865, with Liebig as director. He was issued ‘an annual salary of £1,000 and an immediate cash payment of £5,000 if the company could use Liebig’s name, fame, and capital as a guarantee to raise funds on the London Stock Exchange’.[11] Learning the power of his reputation in the financial markets, Liebig took advantage of the influence it heeded: he utilized his connections and issued countless samples, prioritizing his influential connections like writers, scientists, physicians, and government officials, urging them to invest.[12]

Liebig’s enthusiastic participation in the transnational commodification of foodstuff, and financial stake in its operations until his death in 1873 offers an early example of the intersection between nutritional science and its economic impact on food industries. It is possible that the 1899 rebranding of the product, changing its name to Oxo in the English-speaking world may have contributed to the public divorcing of Liebig’s name from the list of modern multinational organizations with roots in the history of dietetics.[16] While a recent revisiting of the nutritional value of bone broths, produced both at home and on an industrial scale, has left much for scientists and health professionals to grapple with, the roots of these beliefs and the desire for these foodstuffs to be widely available can certainly be traced back to Liebig.

References:

[1] von Liebig, Justus. Animal Chemistry, or Organic Chemistry in Its Application to Physiology and Pathology. John Owen. 1843. P. 20, 92, 167-9, 300-5.; Turner, Bryan S. ‘The Government of the Body: Medical Regimens and the Rationalization of Diet’. British Journal of Sociology, vol. 33, no. 2, 1982, P. 258-9, 268.; Kamminga, Harmke and Andrew Cunningham. ‘Introduction’ in The Science and Culture of Nutrition, 1840-1940. Brill. 1995. P. 5, 7.

[2] Finlay, Mark. ‘Early Marketing of the Theory of Nutrition’ in The Science and Culture of Nutrition, 1840-1940. Brill. 1995. P. 56-7.; Perren, Richard. ‘The Meat and Livestock Trade in Britain, 1850-70’. The Economic History Review, vol. 28, no. 3, 1975, P. 385–400. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2593589.

[3] Beneke, William. ‘On Extractum Carnis’. The Lancet, September 1851. P. 8.

[4] Finlay, Mark R. ‘Quackery and Cookery: Justus Von Liebig’s Extract of Meat and the Theory of Nutrition in the Victorian Age’. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 66, no. 3, 1992, P. 406. JSTOR.; Spang, Rebecca L. The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture. Harvard University Press. 2020.

[5] Brock, Willam H. Justus Von Liebig: The Chemical Gatekeeper, Cambridge University Press, 1997. P. 224-6.

[6] Finlay, ‘Early Marketing’. P. 58.; Brock, Justus von Liebig, P. 226.

[7] Judel, Günther Klaus. ‘Die Geschichte von Liebigs Fleischextrakt. Zur populärste Erfindung des berühmten Chemikers’, Spiegel der Forschung, 1. P. 6-17 cited in Morcillo, Marta García. ‘Antiquity and Modern Nations in the Liebig Trading Cards’ in Antigüedad clásica y naciones modernas en el Viejo y el Nuevo Mundo, Edited by Antonio Duplá Ansuategui, Eleonora Dell’ Elicine, Jonatan Pérez Mostazo. Ediciones Polifemo. 2018, P. 230.; Finlay, ‘Early Marketing’, P. 58.; Brock, Justus Von Liebig, P. 224-229.; Rüger, Jan. ‘OXO: Or, the Challenges of Transnational History’. European History Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 4, Oct. 2010, P. 657–58. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691410376488.

[8] Though never explicitly claimed, the conclusion was strongly implied by Liebig and Charles Boner, see; von Liebig, Justus. Researches on the Chemistry of Food (London, 1847), P. 131-3.; Beneke, ‘On Extractum Carnis’. P. 7-8.; Charles Boner, ‘Extract of Meat’, Popular Science Review, 4 (1865), 292-301.; Hassall, Arthur H. ‘On the Nutritive Value of Liebig’s Extract of Beef, Beef-Tea, and Wine’. The Lancet, July 8th, 1865. P. 49-50.; Hutchison, Robert. Food and the Principles of Dietetics. W. Wood & Co. 1917.; Finlay. ‘Quackery and Cookery’. P. 410.

[9] Finlay. ‘Early Marketing’. P. 55.

[10] Finlay. ‘Early Marketing’. P. 65.

[11] Brock. Justus Von Liebig. P. 226-7.

[12] Finlay. ‘Early Marketing of the Theory of Nutrition’. P. 59.

[13] Nightingale, Florence. Notes on Nursing: What it is, and What it is Not. Harrison. 1859. P. 39.

[14] Nightingale. Notes on Nursing. P. 39.; Hassall, ‘On the Nutritive Value of Liebig’s’. P. 49-50.; von Liebig, Justus. ‘Liebig’s Extract of Meat’. The Lancet, October 21, 1865. P. 469.; Allen and Handburys, ‘To the Editor of The Lancet’. The Lancet, October 21, 1865. P. 469.; Liebig, ‘On the Nutritive Value of “Extractum Carnis”’, The Lancet, November 11, 1865. P. 547.; Child, E. ‘On the Nutritive Value of “Extractum Carnis”’. The Lancet, December 2nd, 1865. P. 633.; Vosper, Thomas. ‘To the Editor of The Lancet’. The Lancet, December 2nd, 1865. P. 633.; von Liebig, Justus. ‘On the Nutritive Value of “Extractum Carnis”’. The Lancet, December 9th, 1865. P. 651.; Vosper, Thomas. ‘On the Nutritive Value of “Extractum Carnis”’.The Lancet, December 23rd, 1865. P. 717.; Hutchison, Food and the Principles. P. 106-9.

[15] Presbrey, Frank. The History and Development of Advertising. Doubleday, Doran & Company. 1968. P. 339, 361, 416, 436.; Kamminga and Cunningham. ‘Introduction’. P. 7.

[16] It is not clear why the name was changed though I speculate this may have been to avoid a decrease in sales due to anti-German sentiment—this trend is best exemplified by the British royal family’s name change from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor in 1917. Vincenzi, Penny. Taking Stock: Over 75 Years of the Oxo Cube. Willow Books. P. 18-9.; Hutchison, Food and the Principles. P. 96-9.

Featured image credit: Liebig “Company’s” Extract of Beef : J. Liebig: this signature on each jar [of the] finest meat flavouring stock for soups, sauces and made dishes / Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, Ltd. Source: Wellcome Collection.